doi.org/10.20986/revesppod.2025.1762/2025

ORIGINAL

Influence of the hereditary factor on the development of hallux abductus valgus: preliminary results of an observational study

Influencia del factor hereditario en el desarrollo del hallux abductus valgus. Resultados preliminares de un estudio observacional

Marta Moreno-Fresco1

Priscila Távara-Vidalón2

1Private Practice. Sevilla, España

2Podiatry Deparment. University of Seville, Seville, Spain

Abstract

Objectives: To describe the frequency of family history in patients with hallux abductus valgus (HAV) and to explore its association with bilaterality, clinical severity, first-ray mobility, and quality of life, without establishing causal relationships.

Patients and methods: A descriptive cross-sectional observational study in which family history of HAV was collected and foot-related quality of life was assessed using the Foot Health Status Questionnaire (FHSQ). Additionally, first-ray dorsiflexion and plantarflexion, first metatarsophalangeal joint (1st MTPJ) extension, and the Foot Posture Index were evaluated in 99 subjects with HAV.

Results: A total of 81.8 % had a family history of HAV in at least one parent, with the mother being the most commonly affected (46.5 %). Participants with bilateral HAV, compared to those with unilateral HAV, showed significant differences in dorsiflexion and plantarflexion of the first ray (p = 0.024; p = 0.035), as well as in social capacity and vitality domains of the FHSQ (p = 0.032; p = 0.009). Extension of the 1st MTPJ decreased, while pain and deformity duration increased significantly with greater HAV severity (p < 0.001; p = 0.013; p < 0.001).

Conclusion: A high familial aggregation of HAV was observed, along with its association with greater bilaterality, higher clinical severity, and worse perception of foot health. Although the cross-sectional design does not allow causal inference, early identification of individuals with a family history could support more personalized preventive and therapeutic interventions.

Keywords: Hallux abductus valgus, first ray, foot, inheritance, family and etiology

Resumen

Objetivos: Describir la frecuencia de antecedentes familiares en pacientes con hallux abductus valgus (HAV) y explorar su asociación con la bilateralidad, la gravedad clínica, la movilidad del primer radio y la calidad de vida, sin establecer relaciones de causalidad.

Pacientes y métodos: Estudio observacional transversal descriptivo en el que se recogieron los antecedentes familiares de HAV y se valoró la calidad de vida y salud del pie con el cuestionario de salud del pie (FHSQ, del inglés Foot Health Status Questionnaire). Además, se valoró la dorsalflexión y plantarflexión del primer radio, la extensión de la 1.ª articulación metatarsofalángica (AMTF) y el Foot Posture Index en 99 sujetos con HAV.

Resultados: El 81.8 % de los sujetos presentaron antecedentes familiares de HAV en al menos uno de los progenitores, siendo la madre el familiar más afectado (46.5 %), Los sujetos con HAV bilateral vs. HAV unilateral presentaron diferencias significativas en la dorsalflexión y plantarflexión del primer radio (p = 0.024; p = 0.035) y en capacidad social y vitalidad del FHSQ (p = 0.032; p = 0.009). La extensión de la 1.ª AMTF disminuyó, y el dolor y la duración de la deformidad aumentaron significativamente a medida que se incrementaba la gravedad (p < 0.001; p = 0.0130; p < 0.001).

Conclusiones: Se observó elevada agregación familiar del HAV y su asociación con mayor bilateralidad, gravedad clínica y peor percepción de la salud del pie. El diseño transversal no permite establecer causalidad, pero su detección precoz de sujetos con antecedentes familiares podría respaldar intervenciones preventivas y terapéuticas más personalizadas.

Palabras claves: Hallux valgus, primer radio, pie, herencia, familia y etiología

Corresponding autor

Priscila Távara-Vidalón

stavara@us.es

Received: 19-09-2025

Accepted: 18-11-2025

Introduction

Hallux abducto valgus (HAV) is a lateral deviation of the great toe that produces subluxation of the 1st metatarsophalangeal joint (MTPJ) with plantarflexion and eversion, medial deviation of the first metatarsal with dorsiflexion and inversion, and is frequently associated with a medial and dorsal prominence of the first metatarsal head known as a bunion(1,2).

Although HAV is not inherited as an isolated entity, several studies have reported high familial aggregation, with positive family histories in 60–90 % of cases(3). Congenital presentations have been described in the literature(3), and in certain family contexts, a possible autosomal dominant inheritance pattern with incomplete penetrance has been suggested, especially when first-degree relatives are affected(4). Likewise, multigenerational patterns and early-onset cases have been reported5, supporting a relevant hereditary component.

Beyond a specific genetic model, it has been demonstrated that foot morphology is heritable, and that structural variables of the first metatarsal, the medial cuneiform, or the hallux may predispose individuals to the development or progression of HAV. The appearance of the deformity in childhood or adolescence1 further reinforces this inherited structural influence.

Moreover, former studies have described a higher frequency of maternal family history, contributing to the hypothesis of a significant familial burden in the clinical expression of the deformity6. It has also been proposed that the higher prevalence in women may reflect sex-related or hormonal modulators5, although this does not imply a single direct hereditary mechanism.

Although factors such as footwear, physical activity, or body mass index (BMI) have been associated with the development or progression of HAV, the presence of the deformity in young individuals with low exposure to these factors suggests that external factors alone are insufficient to explain its onset, reinforcing the relevance of underlying structural and familial components.

Despite the evidence of familial aggregation in HAV, limitations persist regarding its relationship with an individual’s clinical characteristics according to their family history. Therefore, the objective of this study is to describe the frequency of family history in patients with HAV and to explore its association with bilaterality, clinical severity, first-ray mobility, and quality of life, without establishing causal relationships. Understanding this genetic dimension not only improves early diagnosis and prevention in predisposed individuals but also contributes to the development of more individualized and effective therapeutic strategies.

Patients and methods

Study design

We conducted a descriptive, cross-sectional observational study in accordance with STROBE recommendations.

Participants

The sample consisted of adults who attended the Clinical Podiatry Area of Universidad de Sevilla (Seville, Spain) and 2 private clinics in the province of Seville (Spain) between May 2024 and June 2025, provided they met the selection criteria and voluntarily agreed to participate.

Inclusion criterion: individuals presenting HAV who could reliably provide information on the presence of HAV in their parents and grandparents. Exclusion criteria: history of trauma affecting first-ray mobility; previous first-ray surgery; current use of orthopedic or podiatric treatment; and/or systemic, degenerative, or neuromuscular diseases affecting the feet.

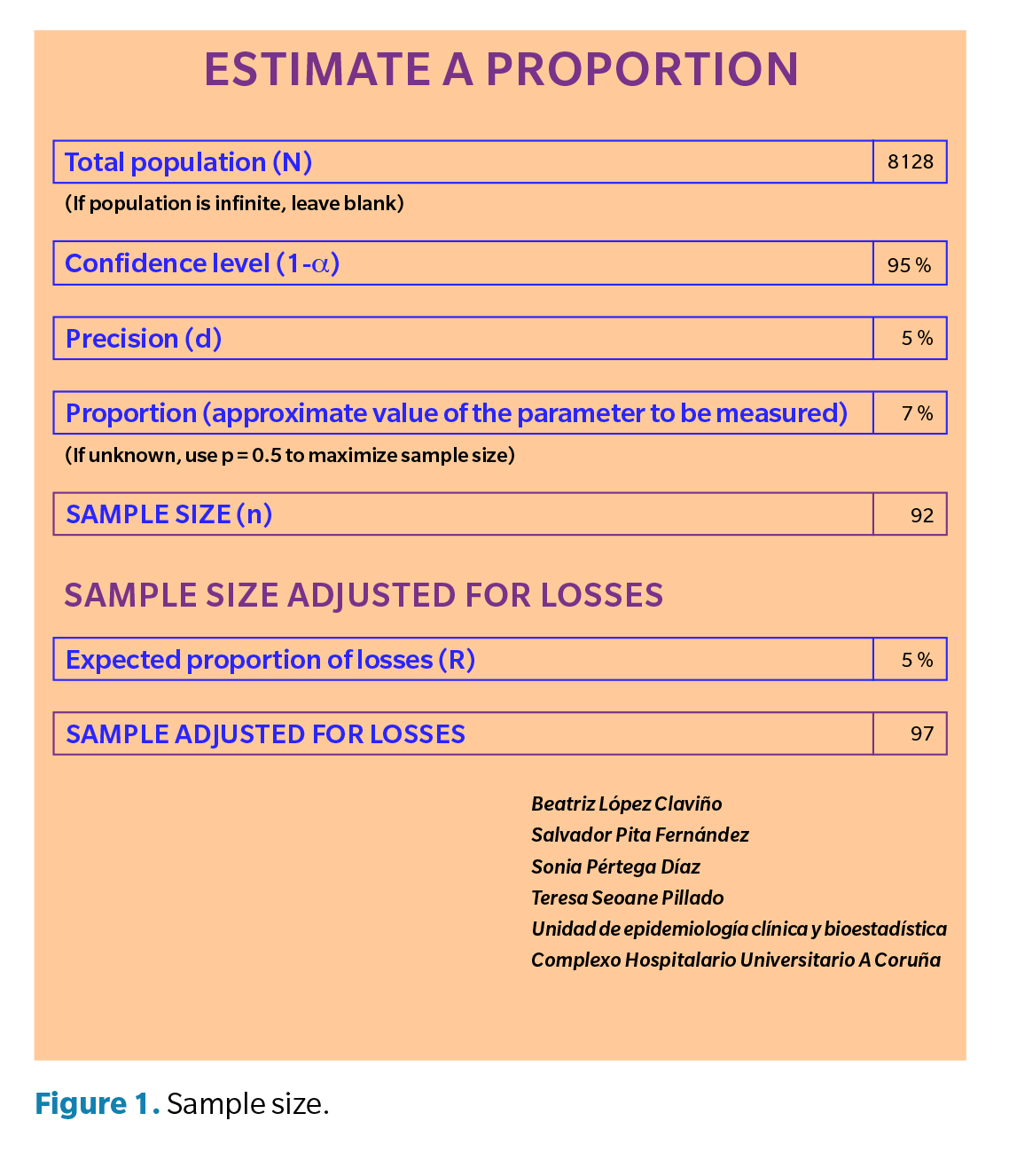

Sample size

Sample size was calculated with a 95 % confidence level, 5 % margin of error, and 5 % expected losses, using as reference the HAV population treated at the Clinical Podiatry Area over the previous 3 years. A minimum of 97 participants was estimated as necessary (Figure 1).

The calculation was oriented toward estimating the frequency of family history, but it was not powered specifically for subgroup comparisons, which is acknowledged as a limitation.

Data collection

Clinical examination

The clinical examination was performed by 2 podiatric examiners (12 and 2 years of experience). Each measurement was conducted once per evaluator, and blinding was not applied due to the clinical observability of the deformity. Subjects who met all inclusion criteria were enrolled, and diagnostic parameters were assessed following the protocol below:

- First-ray mobility: maximum dorsiflexion and plantarflexion range was measured in millimeters with the patient in supine position, ankle relaxed, and subtalar joint in neutral, following previously validated protocols7-9 (Figure 2).

- Extension of the 1st MTPJ: evaluated using a 2-arm goniometer, with the patient supine, the foot relaxed, and the knee extended. From the neutral position, the hallux and distal goniometer arm were taken to maximum extension, allowing the first ray to plantarflex(1).

- Foot Posture Index (FPI): assessed in relaxed bipedal stance, following the protocol described by Redmond et al.10, producing a score for each foot. Normal values range from 0 to +5.

- HAV severity: assessed using the Manchester Scale11, classifying deformity into three grades: Grade 2 (mild), Grade 3 (moderate), Grade 4 (severe)

- Family history of HAV: a structured data collection sheet included specific questions on the presence of HAV across three generations. Targeted anamnesis was conducted by both investigators to document HAV in first-degree relatives (parents) and second-degree relatives (maternal and paternal grandparents), extending to third-degree relatives when responses were positive.

- Quality of life (FHSQ: Foot Health Status Questionnaire): foot-related quality of life was assessed using the Spanish version of the FHSQ(12), which evaluates eight domains: foot pain, foot function, footwear, general foot health, general health, physical activity, social capacity, and vitality Scores were transformed to a 0–100 scale, where 0 indicates the worst and 100 the best possible state. Values were interpreted qualitatively as: very low (0–24.9), low (25–49.9), medium (50–74.4), and high (≥ 75) following Domínguez-Muñoz et al. (12).

Data análisis

IBM® SPSS® Statistics (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) in its most current version was used for the statistical analysis. Descriptive statistics included absolute (N) and relative (%) frequencies, mean, standard deviation, median, and interquartile range. The unit of analysis was the subject (n = 99). Although clinical measurements were taken from both feet in bilateral cases, the data were analyzed per patient, without duplicating observations by foot.

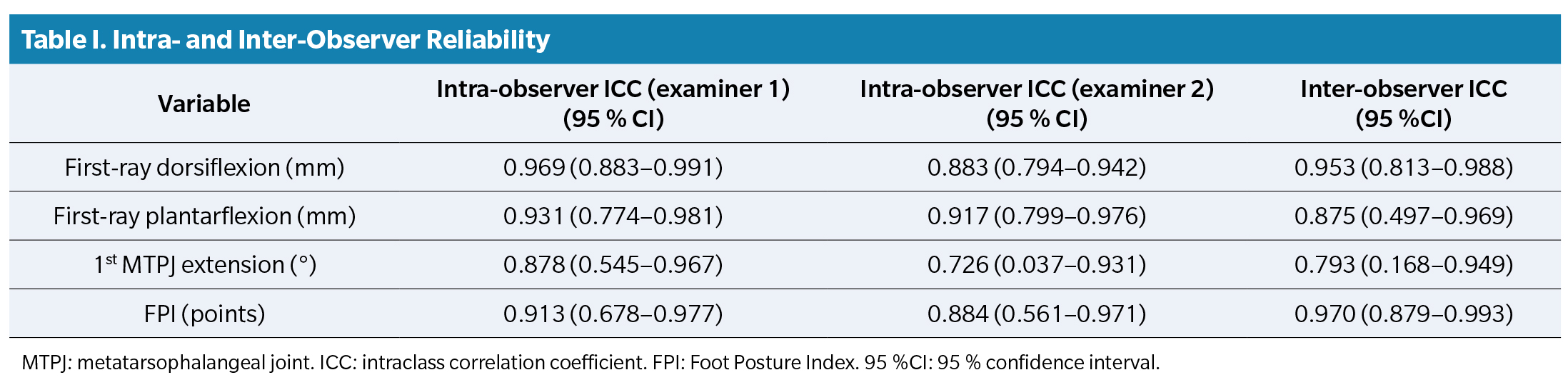

To assess reliability, inter-rater and intra-rater agreement was analyzed using the intraclass correlation coefficient. First-ray mobility, 1st MTPJ extension, and the FPI were measured in 10 randomly selected subjects by two investigators to determine inter-observer reliability. For intra-observer reliability, these same variables were evaluated twice, with a 20- and 30-day interval between measurements. A two-way mixed-effects model, consistency type, and average measures were used to calculate the intraclass correlation coefficient.

For family inheritance data (father, mother, grandparents, aunts/uncles, siblings), frequency analyses and contingency tables were conducted to identify co-occurrence patterns of family history among members. Absolute frequencies (N), relative percentages (%), valid percentages (excluding missing values), and cumulative percentages were calculated for each categorical variable.

Normality was verified using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. To compare clinical and functional variables between unilateral and bilateral HAV subjects, Student’s t-test for independent samples was used when the distribution was normal, and the Mann–Whitney U test when it was not. For comparisons among different HAV severity grades, analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used when data were normally distributed; otherwise, the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test was applied for more than two independent groups. Post-hoc comparisons used the Tukey procedure for variables analyzed by ANOVA, and Dunn’s test with Bonferroni correction for non-parametric variables. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Analyses were bivariate and did not adjust for potential confounders (age, sex, BMI), therefore residual confounding cannot be ruled out.

Results

The sample consisted of 99 subjects with HAV. Twenty-two presented unilateral HAV and 77 bilateral HAV; 76 participants were women and 23 men. Severity distribution was 44 mild, 40 moderate, and 15 severe cases. Mean age was 47.76 ± 15.14 years (range, 20–78), and BMI was 25.45 ± 4.09 (normal weight).

Intraclass correlation coefficient results, together with the 95% confidence intervals, showed good intra-observer and inter-observer reliability (Table 1). The subsample used for this analysis was small (n = 10), resulting in wide confidence intervals.

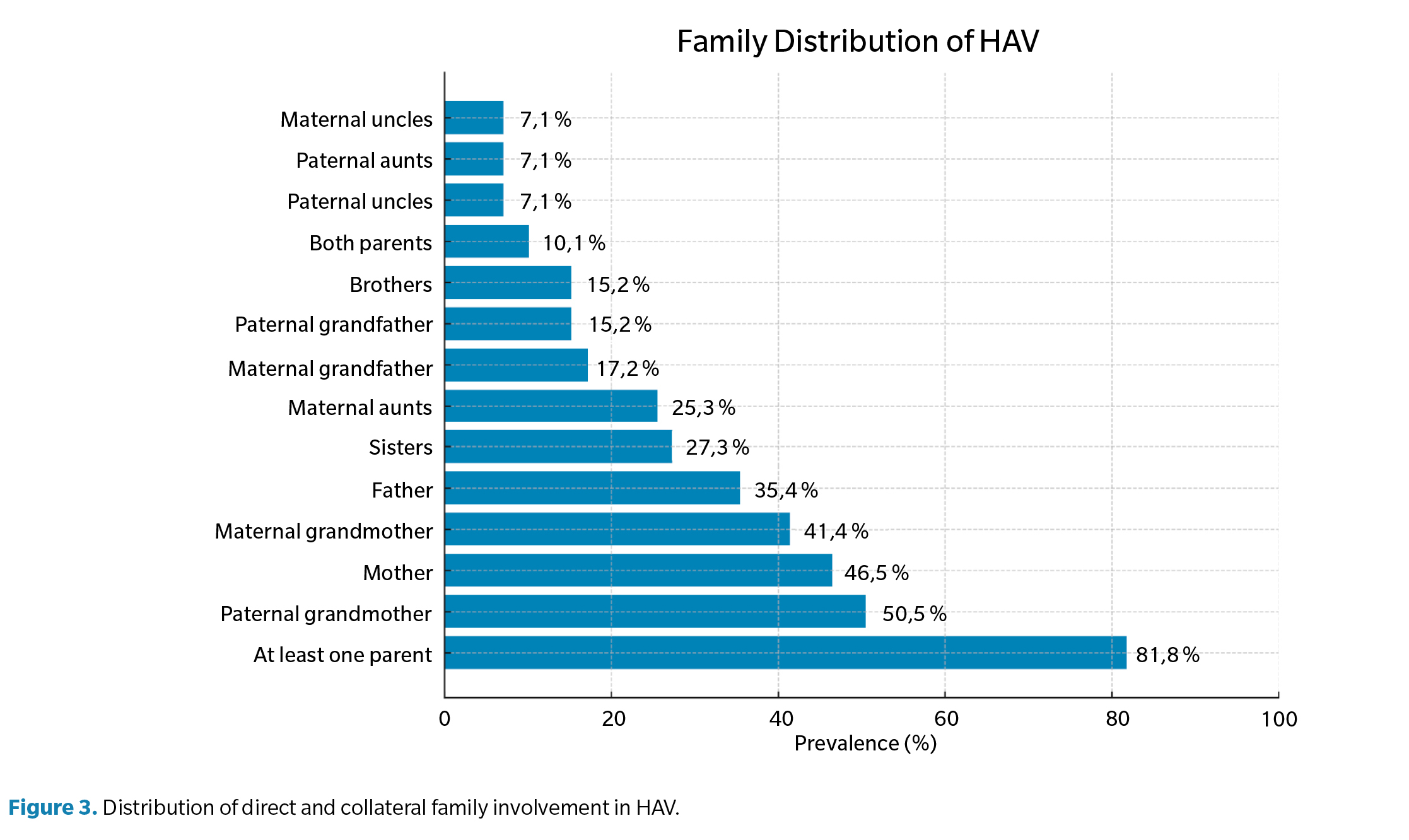

With respect to familial involvement, 81.8% of subjects reported a family history of HAV in at least one parent, with the mother being the most affected relative (46.5 %), followed by the father (35.4 %) and both parents (10.1 %). The paternal grandmother was the most frequently referenced grandparent (50.5 %). In 18.2%, no direct family history was identified, and 39.4 % reported that at least one sibling also had HAV. The complete distribution is shown in Figure 3.

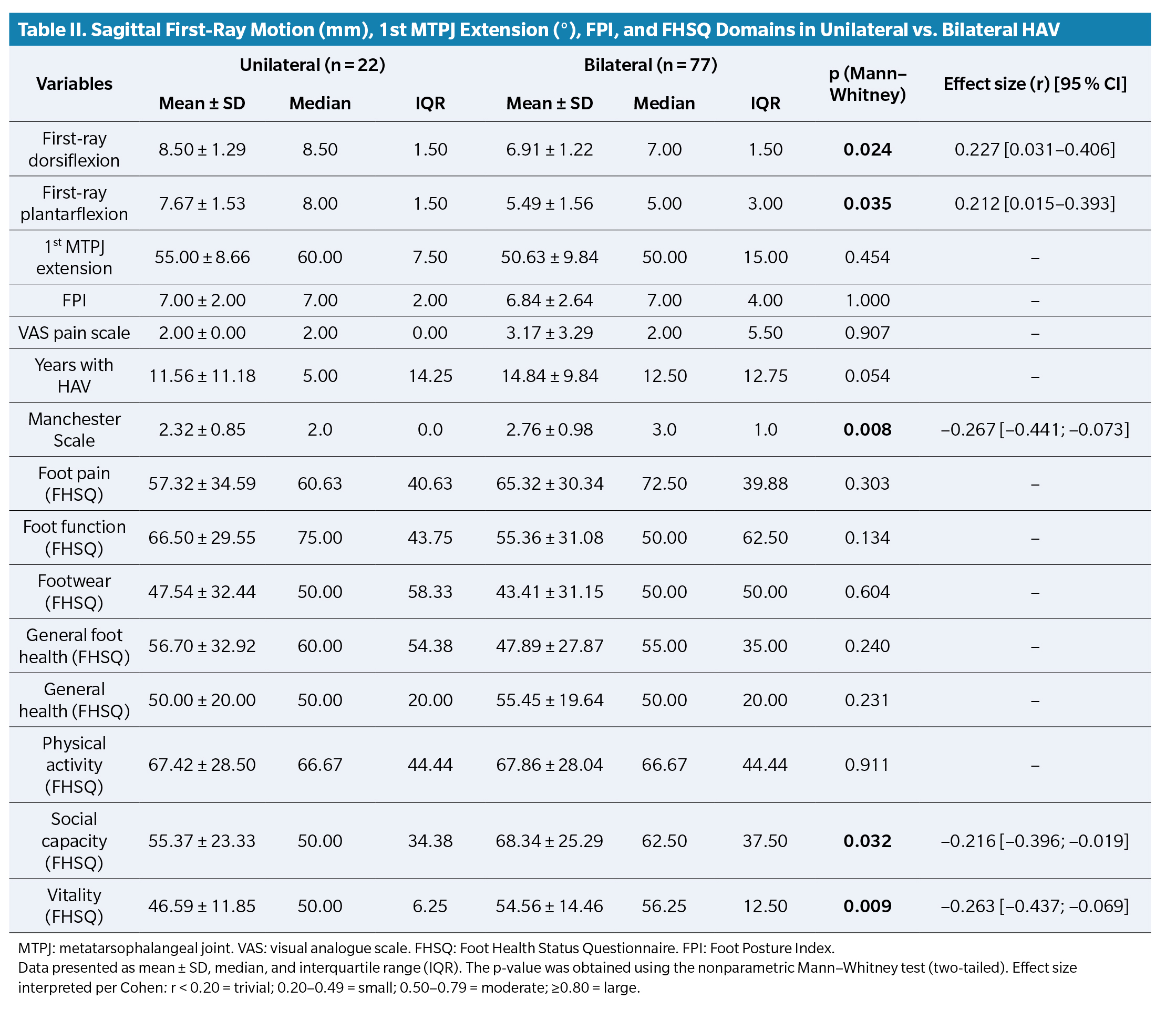

We compared first-ray dorsiflexion and plantarflexion, 1st MTPJ extension, FPI, pain, years with HAV, Manchester Scale score, and the FHSQ domains between unilateral and bilateral HAV subjects (Table 2). Individuals with unilateral HAV showed significant differences compared with bilateral cases in first-ray dorsiflexion and plantarflexion, and in the social capacity and vitality domains of the FHSQ. Unilateral cases exhibited greater dorsiflexion and plantarflexion of the first ray (p = 0.024; p = 0.035), with a 1.50 mm difference in dorsiflexion and 3 mm in plantarflexion. Meanwhile, bilateral cases scored significantly higher in social capacity (p = 0.032) and vitality (p = 0.009) by 12.5 and 6.25 points, respectively. Bilateral subjects also showed longer deformity duration and greater structural severity according to the Manchester Scale (p = 0.008).

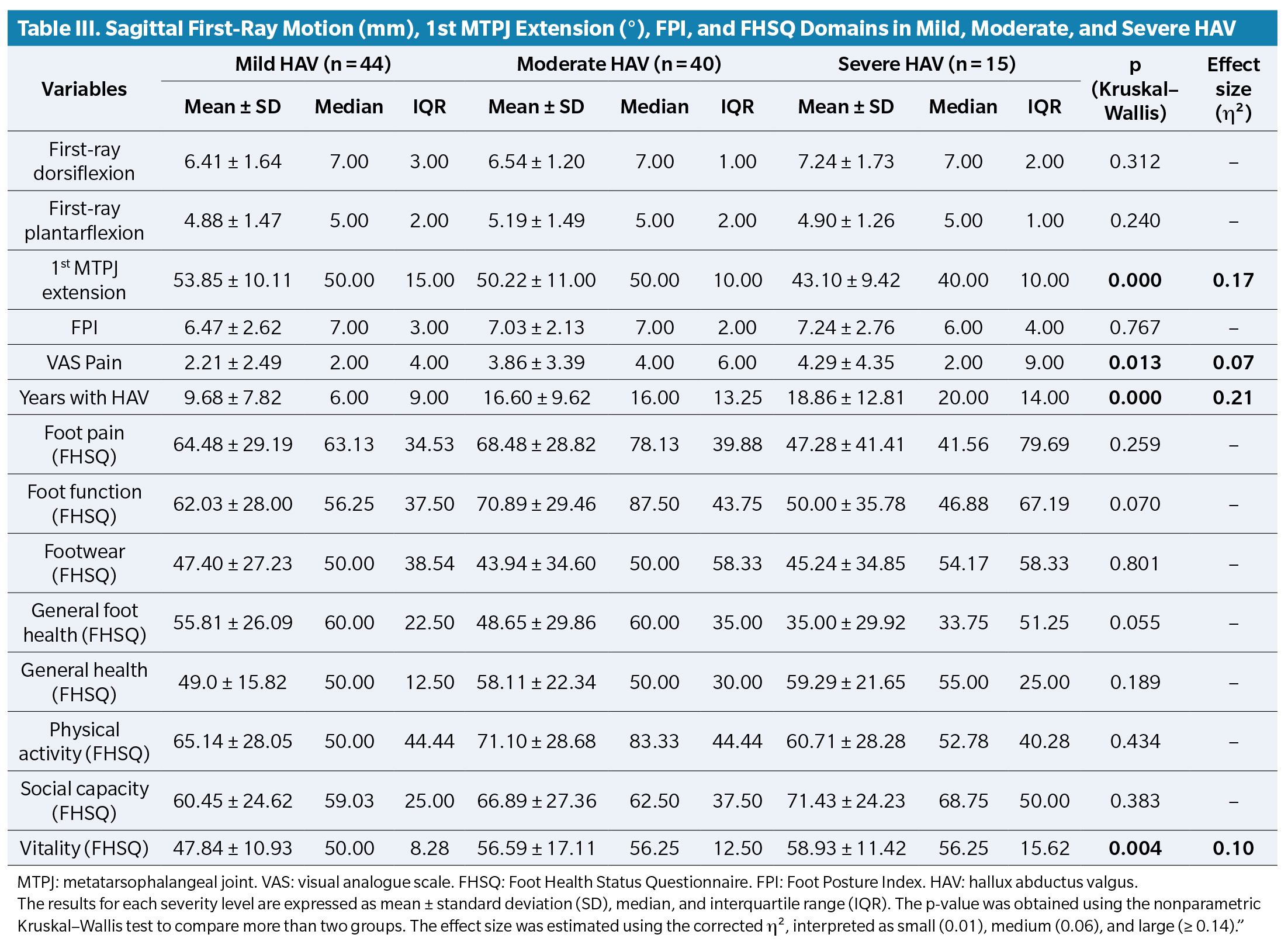

When comparing HAV severity grades (Table 3), significant differences were found in: 1) 1st MTPJ extension (p < 0.001), which decreased as severity increased, with ~10° difference between extremes; 2) Foot pain, with mild cases differing by 2 points from moderate cases, while severe cases displayed a wide interquartile range (9), reflecting notable variability (p = 0.013); 3) Years of deformity evolution, which increased progressively: median 6 years (mild), 16 (moderate), and 20 (severe), with more than a 10-year increase across groups (p < 0.001); 4) Vitality domain of the FHSQ, with moderate and severe cases scoring higher medians (56.25) than mild cases (50) with slightly wider interquartile ranges (p = 0.004). In contrast, median values for first-ray dorsiflexion, plantarflexion, and FPI were similar across severity groups, with narrow interquartile ranges.

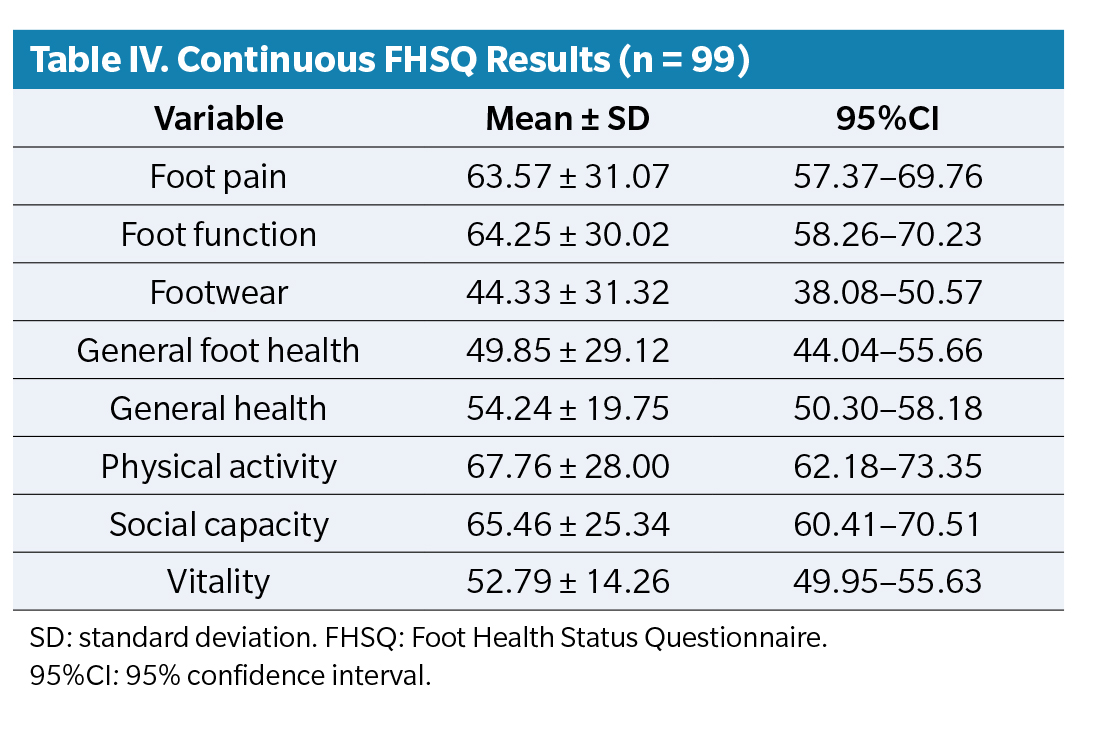

Regarding foot-related quality of life (FHSQ) (n = 99), continuous scores are presented in Table 4. The lowest mean scores were in the “Footwear” and “General foot health” domains.

Discussion

The primary endpoint of this study was to describe the frequency of family history among patients with HAV and to explore its association with bilaterality, clinical severity, first-ray mobility, and quality of life.

The results demonstrated a high degree of familial aggregation: 81.8% reported direct family history, with the mother being the most frequently affected relative. Additionally, notable familial aggregation was observed in previous generations (over 50% of paternal grandmothers and 41 % of maternal grandmothers) and among siblings, suggesting intergenerational transmission. Subjects with bilateral HAV presented greater clinical severity, longer disease duration, and distinct functional differences compared with unilateral cases. Regarding quality of life, the most affected FHSQ domains were “Footwear” and “General foot health”, with significant differences also found in vitality and social capacity.

The methodology, based on collecting family history across three generations, aligns with that used by Piqué-Vidal et al. (2), differing from earlier studies focused solely on first-degree family history, such as those by Hardy & Clapham(13) and Glynn et al. (14). In the study by Coughlin & Roger(15), data collection focused exclusively on the maternal line through direct anamnesis with the participant’s mother. Thus, the methodology used in our study allowed not only registration of the presence of HAV in direct relatives but also assessment of the pattern of occurrence across generations, providing a broader view of the potential hereditary component of this deformity.

The results obtained resemble those of the study by Hardy and Clapham(13), who as early as 1951 identified a family history in 63 % of 91 patients with HAV. Similarly, Glynn et al. (14) in 1980 observed a 68 % prevalence among 41 patients, and Coughlin and Roger(15) in 1995, in a study focused on juvenile HAV, reported that 94% of the 31 mothers of participants also had the deformity. Finally, in the study by Piqué-Vidal et al. (2), a positive family history was found in 68 % of the 350 cases analyzed.

The maternal predominance observed and the high familial aggregation found in our results are consistent with previous studies describing a relevant familial component in HAV(15,16). Although some authors have proposed a possible autosomal dominant inheritance pattern with incomplete penetrance, such claims come from genealogical studies or specific genetic analyses(1,4,7). Given the cross-sectional design of our study, it is not possible to evaluate hereditary transmission models or establish causal genetic mechanisms; therefore, our results should be interpreted solely as evidence of high familial aggregation, without confirming a specific inheritance pattern. The more frequent involvement of women (mothers and grandmothers) suggests a possible interaction between genetic and hormonal factors. Nix et al. (18), in a systematic review, also pointed to a significant familial predisposition in the development of HAV, independent of extrinsic mechanical factors. Studies such as those by Perera et al. (17), Glasoe et al. (19), and Shinohara et al. (20) indicate that certain anatomical and biomechanical characteristics are heritable—such as the shape of the first metatarsal head, first-ray hypermobility, or increased rearfoot valgus—and could therefore contribute to early HAV onset. This would explain why some individuals develop the deformity at a young age, even before 20 years old, without exposure to narrow footwear or high heels, as occurred in some cases within our sample.

Of the 99 subjects analyzed, 77 presented bilateral HAV, with a mean deformity progression of 15.57 years. Among these, 81.8% reported a positive direct family history (father or mother), suggesting a possible association between inheritance and greater clinical burden. This finding aligns with Coughlin et al. (5), who observed that bilateral and juvenile HAV forms tended to occur in patients with strong familial aggregation and tended to progress with greater severity and clinical deterioration. Additionally, Manchester Scale scores were higher in the bilateral group, reflecting a greater degree of observable deformity. These results reinforce a possible relationship between family patterns and more severe clinical presentation of HAV and may help identify cases at higher risk of progression.

Regarding static examination, first-ray movement showed greater dorsiflexion than plantarflexion in HAV subjects (dorsiflexion: 6.60 mm ± 0.57 vs. plantarflexion: 5.07 ± 0.65). These findings align with several authors who have reported greater dorsiflexion range in individuals with this deformity(7,21,22,23,24,25,26,27). Bilateral HAV subjects showed significantly greater first-ray dorsiflexion compared with unilateral subjects, which may be interpreted as greater functional rigidity of the first metatarsal. This finding is consistent with the biomechanical evolution described by Morton(28), where initial hypermobility of the first ray may eventually give rise to adaptive rigidity due to progressive joint deterioration.

Regarding 1st MTPJ extension, results showed a slight reduction from normal values (50.94° ± 0.13), compared with those found in individuals with normal feet in the 2021 study by Távara-Vidalón et al. (9) (66.67° ± 2.56). Comparing mild, moderate, and severe HAV groups revealed a significant decrease in 1st MTPJ extension as severity increased, indicating greater limitation or joint stiffness in advanced HAV forms, consistent with the degenerative nature of the deformity in later stages. Finally, FPI results showed a general trend toward more pronated values. This finding agrees with prior studies suggesting that excessive pronation can alter first-ray biomechanics and facilitate hallux deviation(29,31). However, more evidence is needed to confirm this association in hereditary contexts.

Regarding foot-related quality of life measured by the FHSQ, descriptive results showed moderate impairment in the overall sample (Table 3), with the most affected domains being “Footwear” and “General foot health.” Mean overall scores were 56.60 among unilateral and bilateral HAV subjects and 56.86 among mild, moderate, and severe cases, indicating moderate impairment. Analyzing specific FHSQ domains revealed the following statistically significant differences: when comparing unilateral vs. bilateral HAV, the bilateral group showed higher scores in social capacity (p = 0.032) and vitality (p = 0.009). This could be explained by longer disease duration, which may lead to better adaptation to functional limitations. When comparing HAV severity, vitality scores were again higher in moderate and severe cases (56.25 points) compared with mild cases (50 points) (p = 0.004). This could be due to similar mechanisms—better acceptance of the condition, prolonged adaptation, or the fact that functional decline does not always translate into a direct impact on perceived energy levels. These interpretations, however, must be qualified due to the small sample size in the severe and unilateral groups.

Studies by López López et al. (32) and Palomo et al. (33), using the FHSQ in subjects with varying HAV degrees according to the Manchester Scale, found a negative impact on quality of life as HAV severity increased. Bilateral HAV subjects showed a pain score of 72.50, indicating moderate pain, whereas severe HAV subjects scored 41.56, indicating more intense pain likely related to joint pressure, metatarsal overload, and footwear difficulties.

Functional scores were 46.88 in severe HAV and 50 in bilateral HAV, reflecting mild-to-moderate limitations in daily activities. Menz and Lord(34) demonstrated how HAV, especially bilateral cases, interferes with gait biomechanics, propulsion, and balance. Menz et al. (35) and Nix et al. (36) reported that even mild HAV significantly affects foot function and perceived well-being. Furthermore, deformity duration showed an inverse correlation with FHSQ scores, indicating that greater HAV chronicity is associated with worse quality of life(35). General foot health was also diminished in severe HAV cases.

The footwear domain, with a median score of 50 points, was among the lowest rated, reflecting moderate impairment. This is consistent with the literature, which highlights difficulty finding suitable footwear—due to bunion prominence, hallux deviation, or forefoot width—as a main complaint among HAV patients, as described by Dufour et al. (37).

From a clinical perspective, these findings have significant implications. Identifying a family history of HAV in asymptomatic patients or those in early deformity stages may justify early conservative interventions, such as customized foot orthoses, appropriate footwear, or targeted muscle-strengthening programs(38,39,40). Prevention should focus particularly on young individuals with a positive family background, using longitudinal follow-up protocols similar to those applied in hereditary conditions with high functional impact.

The results of this study should be interpreted cautiously due to several limitations. The main limitation is the lack of objective clinical confirmation of family history, which relied solely on directed anamnesis. This may introduce recall bias and misclassification, especially in older generations. Nonetheless, criteria were established to maximize reliability by prioritizing participants able to provide accurate family data, given the study’s focus on HAV heredity. Secondly, the sample size was adequate to estimate family history frequency but was not calculated specifically for subgroup comparisons, limiting statistical power. Future studies should aim to homogenize groups to improve analytic consistency. Additionally, as the analyses were bivariate without adjustment for confounders (age, sex, BMI), residual confounding cannot be excluded. The subsample used for reliability testing was small (n = 10), resulting in wide confidence intervals that must be interpreted cautiously. These factors do not invalidate the findings but should be acknowledged in their interpretation.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates high familial aggregation and associations between family history of HAV and greater bilaterality, clinical severity, and poorer perceived foot health. Although these findings do not establish causality, they reinforce the importance of clinical screening in individuals with a family history to optimize early detection and contribute to developing more personalized preventive and therapeutic strategies.

Conflicts of interest

None declared

Funding

None declared

Ethic statement

The investigation adhered to current bioethical regulations, the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Association), the Council of Europe Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine, and the UNESCO Declaration on Human Rights. The present study had a favorable ruling from the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the University of Seville (ID: 2000-N23). All participants signed informed consent, and authorization was obtained from the Clinical Podiatry Area of the University of Seville

Authors’ contributions

study conception and design: MMF, PTV: Data collection: MMF, PTV

Analysis and interpretation of results: MMF, PTV: Drafting and preparation of the initial manuscript: MMF, PTV: Final review: MMF, PTV

References

- Munuera-Martínez PV. El primer radio. Biomecánica y Ortopodología. 2.a ed. Santander: Exa Editores SL; 2012. 254 p.

- Piqué-Vidal C, Solé MT, Antich J. Hallux valgus inheritance: pedigree research in 350 patients with bunion deformity. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2007;46(3):149-54. DOI: 10.1053/j.jfas.2006.10.011.

- Giannestras N. Trastornos del pie. Barcelona: Salvat Editores SA; 1979. 58-59 p.

- Johnston O. Further studies of the inheritance of hand and foot anomalies. Clin Orthop. 1956;8:146-60.

- Coughlin MJ, Jones CP. Hallux valgus: Demographics, etiology, and radiographic assessment. Foot Ankle Int. 2007;28(7):759-77. DOI: 10.3113/FAI.2007.0759.

- Perez Boal E, Becerro de Bengoa Vallejo R, Fuentes Rodriguez M, Lopez Lopez D, Losa Iglesias ME. Geometry of the proximal phalanx of hallux and first metatarsal bone to predict hallux abducto valgus: A radiological study. PLoS One. 2016;11(11):e0166197. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0166197.

- Munuera-Martínez PV, Távara-Vidalón P, Monge-Vera MA, Sáez-Díaz A, Lafuente-Sotillos G. The validity and reliability of a new simple instrument for the measurement of first ray mobility. Sensors (Basels). 2020;20(8):2207. DOI: 10.3390/s20082207.

- Távara Vidalón P, Lafuente Sotillos G, Manfredi Márquez MJ, Munuera-Martínez PV. Movilidad normal del primer radio en los planos sagital y frontal. Rev Esp Podol. 2021;32(1):27-35. DOI: 10.20986/revesppod.2021.1600/2021.

- Távara-Vidalón P, Lafuente Sotillos G, Munuera-Martínez PV. Movimiento del primer radio en sujetos con hallux limitus vs. sujetos con pies normales. Rev Esp Podol. 2021;32(2):116-22.

- Redmond AC, Crosbie J, Ouvrier RA. Development and validation of a novel rating system for scoring standing foot posture: The Foot Posture Index. Clin Biomech Bristol Avon. 2006;21(1):89-98. DOI: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2005.08.002.

- Garrow AP, Papageorgiou A, Silman AJ, Thomas E, Jayson MI, Macfarlane GJ. The grading of hallux valgus. The Manchester Scale. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2001;91(2):74-8. DOI: 10.7547/87507315-91-2-74.

- Domínguez-Muñoz FJ, Garcia-Gordillo MA, Diaz-Torres RA, Hernandez-Mocholi MÁ, Villafaina S, Collado-Mateo D, et al. Foot Health Status Questionnaire (FHSQ) in Spanish people with type 2 diabetes mellitus: Preliminary values study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(10):3643. DOI: 10.3390/ijerph17103643.

- Hardy RH, Clapham JCR. Observations on hallux valgus. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1951;33-B(3):376-91. DOI: 10.1302/0301-620X.33B3.376.

- Glynn MK, Dunlop JB, Fitzpatrick D. The Mitchell distal metatarsal osteotomy for hallux valgus. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1980;62-B(2):188-91. DOI: 10.1302/0301-620X.62B2.7364833.

- Coughlin MJ. Roger A. Mann Award. Juvenile hallux valgus: Etiology and treatment. Foot Ankle Int. 1995;16(11):682-97. DOI: 10.1177/107110079501601104.

- Nery C, Coughlin MJ, Baumfeld D, Ballerini FJ, Kobata S. Hallux valgus in males--part 1: Demographics, etiology, and comparative radiology. Foot Ankle Int. 2013;34(5):629-35. DOI: 10.1177/1071100713475350.

- Perera AM, Mason L, Stephens MM. The pathogenesis of hallux valgus. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(17):1650-61. DOI: 10.2106/JBJS.H.01630.

- Nix S, Smith M, Vicenzino B. Prevalence of hallux valgus in the general population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Foot Ankle Res. 2010;3:21. DOI: 10.1186/1757-1146-3-21.

- Glasoe WM, Nuckley DJ, Ludewig PM. Hallux valgus and the first metatarsal arch segment: A theoretical biomechanical perspective. Phys Ther. 2010;90(1):110-20. DOI: 10.2522/ptj.20080298.

- Shinohara M, Yamaguchi S, Ono Y, Kimura S, Kawasaki Y, Sugiyama H, et al. Anatomical factors associated with progression of hallux valgus. Foot Ankle Surg. 2022;28(2):240-4. DOI: 10.1016/j.fas.2021.03.019.

- Kimura T, Kubota M, Taguchi T, Suzuki N, Hattori A, Marumo K. Evaluation of first-ray mobility in patients with hallux valgus using weight-bearing CT and a 3-D analysis system: A comparison with normal feet. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2017;99(3):247-55. DOI: 10.2106/JBJS.16.00542.

- Klaue K, Hansen ST, Masquelet AC. Clinical, quantitative assessment of first tarsometatarsal mobility in the sagittal plane and its relation to hallux valgus deformity. Foot Ankle Int. 1994;15(1):9-13. DOI: 10.1177/107110079401500103.

- Lee KT, Young K. Measurement of first-ray mobility in normal vs. hallux valgus patients. Foot Ankle Int. 2001;22(12):960-4. DOI: 10.1177/107110070102201206.

- Swanson JE, Stoltman MG, Oyen CR, Mohrbacher JA, Orandi A, Olson JM, et al. Comparison of 2D-3D measurements of hallux and first ray sagittal motion in patients with and without hallux valgus. Foot Ankle Int. 2016;37(2):227-32. DOI: 10.1177/1071100715604238.

- King DM, Toolan BC. Associated deformities and hypermobility in hallux valgus: an investigation with weightbearing radiographs. Foot Ankle Int. 2004;25(4):251-5. DOI: 10.1177/107110070402500410.

- Faber FW, Kleinrensink GJ, Verhoog MW, Vijn AH, Snijders CJ, Mulder PG, et al. Mobility of the first tarsometatarsal joint in relation to hallux valgus deformity: Anatomical and biomechanical aspects. Foot Ankle Int. 1999;20(10):651-6. DOI: 10.1177/107110079902001007.

- Glasoe WM, Allen MK, Saltzman CL. First ray dorsal mobility in relation to hallux valgus deformity and first intermetatarsal angle. Foot Ankle Int. 2001;22(2):98-101. DOI: 10.1177/107110070102200203.

- Morton D. Hypermobility of the first metatarsal bone: The interlinking factor between metatarsalgia and longitudinal arch strains. J Bone Joint Surg. 1928;10(2):187-96.

- Evans AM, Copper AW, Scharfbillig RW, Scutter SD, Williams MT. Reliability of the foot posture index and traditional measures of foot position. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2003;93(3):203-13. DOI: 10.7547/87507315-93-3-203.

- Wagner E, Wagner P, Pacheco F, López M, Palma F, Guzmán-Venegas R, et al. Biomechanical cadaveric evaluation of the role of medial column instability in hallux valgus deformity. Foot Ankle Int. 2022;43(6):830-9. DOI: 10.1177/10711007221081461.

- Eustace S, O’Byrne J, Stack J, Stephens MM. Radiographic features that enable assessment of first metatarsal rotation: The role of pronation in hallux valgus. Skeletal Radiol. 1993;22(3):153-6. DOI: 10.1007/BF00206143.

- López López D, Callejo González L, Losa Iglesias ME, Saleta Canosa JL, Rodríguez Sanz D, Calvo Lobo C, et al. Quality of life impact related to foot health in a sample of older people with hallux valgus. Aging Dis. 2016;7(1):45-52. DOI: 10.14336/AD.2015.0914.

- Palomo-López P, Becerro-de-Bengoa-Vallejo R, Losa-Iglesias ME, Rodríguez-Sanz D, Calvo-Lobo C, López-López D. Impact of Hallux Valgus related of quality of life in Women. Int Wound J. 2017;14(5):782-5. DOI: 10.1111/iwj.12695.

- Menz HB, Lord SR. Gait instability in older people with hallux valgus. Foot Ankle Int. 2005;26(6):483-9. DOI: 10.1177/107110070502600610.

- Menz HB, Roddy E, Thomas E, Croft PR. Impact of hallux valgus severity on general and foot-specific health-related quality of life. Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63(3):396-404. DOI: 10.1002/acr.20396.

- Nix SE, Vicenzino BT, Collins NJ, Smith MD. Characteristics of foot structure and footwear associated with hallux valgus: A systematic review. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2012;20(10):1059-74. DOI: 10.1016/j.joca.2012.06.007.

- Dufour AB, Casey VA, Golightly YM, Hannan MT. Characteristics associated with hallux valgus in a population-based foot study of older adults. Arthritis Care Res. 2014;66(12):1880-6. DOI: 10.1002/acr.22391.

- Castellini JLA, Chan DM, Ratti MFG. Biokinetic gait differences between Hallux valgus patients and asymptomatic subjects. Gait Posture. 2025;117:212-9. DOI: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2024.12.027.

- Massaad SO, Elgaili Salah S, Dafaalla Alamin K, Elafef Mahgoob E. Hallux deformity influence – quality of life. Int J Curr Res Med Sci. 2022;8(10):1-7. DOI: 10.22192/ijcrms.2022.08.10.001.

- Zhou W, Jia J, Qu HQ, Ma F, Li J, Qi X, et al. Identification of copy number variants contributing to hallux valgus. Front Genet. 2023;14:1116284. DOI: 10.3389/fgene.2023.1116284.