doi.org/10.20986/revesppod.2026.1799/2025

RESEARCHER’S CORNER

Scientific knowledge II: inductivism versus falsificationism

El conocimiento científico II: inductivismo vs. falsacionismo

Javier Pascual Huerta1

1Clínica del Pie Elcano. Bilbao, España

Correspondence

Javier Pascual Huerta

javier.pascual@hotmail.com

Received: 29-09-2025

Accepted: 02-12-2025

In the previous article in this section, we discussed scientific knowledge through the lens of scientific realism and the pessimistic meta-induction, questioning whether scientific knowledge truly approaches reality or not. These ideas from the philosophy of science can be linked to the concept of falsificationism introduced by the Austrian philosopher Karl Popper (1902–1994) in the 20th century. This theory of science and its behavior emerged as a response to the inductivism of the Vienna Circle, which was the dominant theory at the beginning of the century. Between 1924 and 1936, a group of scientists and philosophers who met periodically at the University of Vienna began to reflect on what the proper method of science should be. They proposed induction as the scientific method: moving from repeated particular observations to general knowledge, that is, a theory. In the history of foot and ankle research, there are many examples of inductivism as a method for generating scientific knowledge. In 2011, Aragón-Sánchez et al.(1) published a study evaluating the combination of plain radiography and the clinical Probe-to-Bone (PTB) test for diagnosing osteomyelitis in diabetic patients with foot ulcers. The authors’ hypothesis was that the combination of positive results from these tests could be sufficient to diagnose osteomyelitis in such patients. They studied 356 episodes in 338 diabetic patients with foot ulceration and infection, calculating the sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values of combining these two tests for the diagnosis of osteomyelitis, using histopathological bone analysis as the reference standard. The values obtained were a sensitivity of 0.97, specificity of 0.92, positive predictive value of 0.97, and negative predictive value of 0.93, leading the authors to conclude that osteomyelitis can be reliably diagnosed when both tests (PTB and plain radiography) are positive. This is an inductive example. The inductive method works through the accumulation of knowledge and is based on the intuitive idea that, as data confirming a theory accumulate, the probability of that theory being true increases.

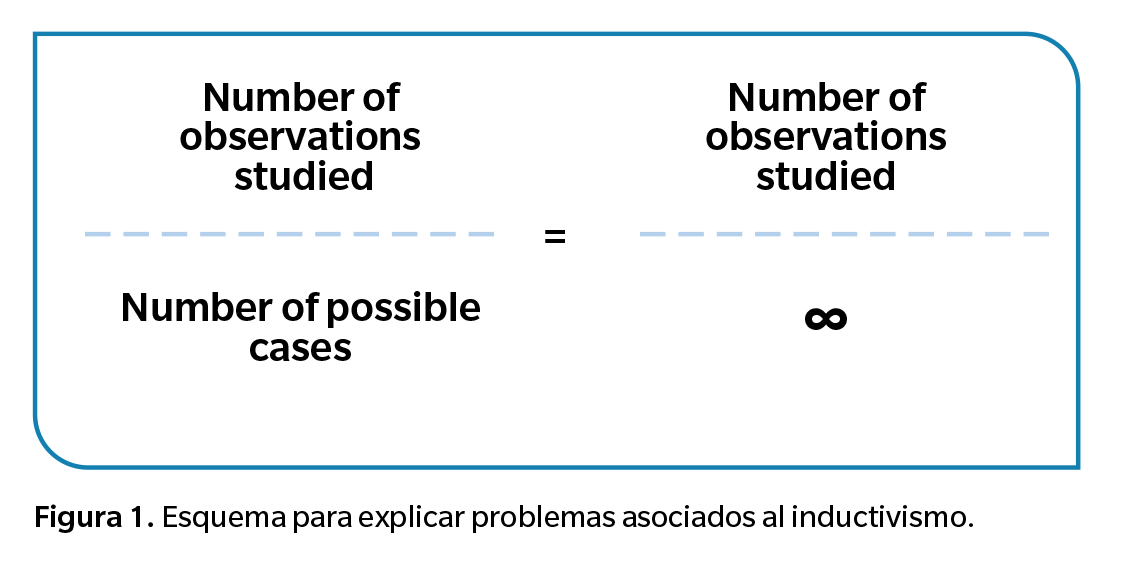

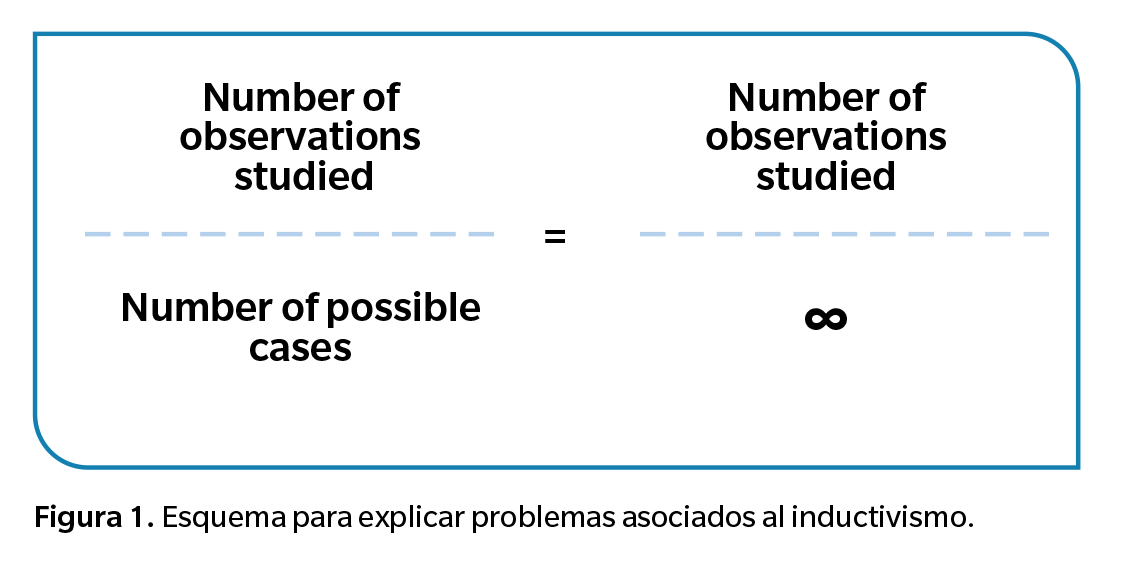

However, although induction may be a path for advancing scientific knowledge, the history of science has shown that scientific theories do not tend to be formed through induction. Karl Popper, in his work Logik der Forschung (1935) (The Logic of Scientific Discovery), strongly criticized inductivism, disagreeing with it as a system for advancing science. The major problem associated with inductivism is what is known as the “inductive leap”: moving from particular observations to a universal law or theory involves an almost insurmountable leap of faith. Why? If we consider past observations of a given phenomenon and the future observations of that same phenomenon in the universe, the number of observations is infinite or tends toward infinity. Our observations of a repeated phenomenon, regardless of how many they are, will always be zero when compared with all the observations that have occurred and will occur in the universe regarding that same phenomenon, because the denominator is infinite (Figure 1). Inductive reasoning is based on the assumption that observed cases are representative of all cases, and for Popper this assumption is a common source of error or logical fallacy. If we consider past cases throughout history and future cases of infected diabetic foot ulcers, the number of observations supporting a hypothesis is irrelevant, because it will always be negligible compared with the total potential number of cases (past and future).

For Popper, it is impossible to verify universal hypotheses through induction. Theories can never be empirically proven. What does this mean? No amount of observational evidence can ever definitively corroborate a theory. It is always possible that future observations will contradict it; therefore, theories can only be provisionally corroborated through research. In fact, the opposite is true: theories can be empirically refuted, they can be falsified (hence the term falsificationism). Empirical evidence can demonstrate that a theory is false, but it cannot demonstrate that it is true. In other words, theories can be falsified but not verified(2).

Of note, Popper assumes that no theory can explain absolute truth (a point where falsificationism aligns with pessimistic meta-induction) and that science progressively brings us closer to reality but never fully reveals it. For him, theories are always accepted provisionally until they are falsified by new evidence emerging from research. For example, if Johannes Kepler’s theory had been completely correct, Newton would not have appeared; if Newton’s theory had been completely correct, Einstein would not have appeared; if Einstein’s theory had been completely correct, Stephen Hawking would not have appeared, and so on. Therefore, theories, when tested, may “withstand” empirical scrutiny; that is, if research does not contradict the theory, it is not refuted or falsified, but this does not make it true. For Popper, a theory is accepted provisionally until it is fully or partially falsified and replaced by a new theory. In short, scientific hypotheses can only be refuted or falsified; they can never be confirmed. Thus, only those hypotheses that repeatedly withstand strong attempts at refutation remain provisionally accepted.

An interesting aspect of this view is that hypotheses are not initially generated by data but are instead invented or conceived by researchers, involving a creative or imaginative component. Hypotheses are invented by scientists to account for observations that form part of the problem the hypothesis seeks to solve. A hypothesis is an idea, and the creation of ideas requires imagination. This imagination cannot arise from nothing; there must be a basis upon which imagination operates: prior observation and experimentation. From this foundation, the scientist creates or formulates a theory with associated hypotheses, and it is at this stage that inductivism may play a more prominent role. Subsequently, once the hypothesis is formulated, empirical evidence is obtained for or against it, and it is evaluated in light of the evidence and critical arguments that help determine its acceptability(2,3).

It is important to understand that if an experimental result shows that a prediction derived from a hypothesis is true, it is then possible to formulate an inductive argument in favor of the hypothesis. That is, when scientific hypotheses are experimentally confirmed, they are the conclusion of an inductive argument, which makes their truth only probable. However, to refute a hypothesis, it is sufficient for the prediction to be false, because refutation relies on a deductive argument. Deductive reasoning ensures that a hypothesis is false, which is not the case when a hypothesis appears to be true. To justify a hypothesis, even if the prediction is fulfilled, we can only be certain up to a point; in contrast, to refute a hypothesis when the prediction fails, we can be completely certain of the refutation. The key is that justification relies on an inductive argument, whereas refutation relies on a deductive one(4).

Nevertheless, despite the significant impact falsificationism had on the philosophy of science during the 20th century, it also has limitations and critics. One important criticism is that science and scientists do not work by automatically falsifying and discarding theories. In practice, scientists almost never discard a theory because of a contradictory experiment; in fact, such contradictions are commonly used to “improve” or “refine” the existing theory rather than discard it, or imperfect theories are accepted as long as no better alternative exists. This phenomenon is precisely described by Kuhn in his book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962), where he discusses paradigm formation and subsequent crises.

In conclusion, these ideas from the philosophy of science may seem extremely tedious to researchers, but they are important. Why? First, if we are aware that we do not operate inductively, that we cannot firmly establish a hypothesis or even probabilistically affirm it, we will adopt a more humble attitude and focus more on identifying errors in the theories we currently use than on seeking easy confirmatory examples. Second, does this mean that no scientific theory is true? Popper’s own answer is: “we will never know.” Popper believed that no matter how advanced knowledge becomes, we will always remain far from the truth. Science is the instrument we use to approach truth, even though we can never be certain of it. But precisely therein lies its virtue: if we had complete certainty, we would stop searching, stop investigating, and stop doing science.

References