doi.org/10.20986/revesppod.2025.1744/2025

ORIGINAL

Relationship between normal mobility of the first ray of the foot and low back pain. Cross-sectional observational study

Asociación entre la movilidad del primer radio del pie y el dolor lumbar: estudio observacional transversal

Patricia Granados-Gómez1

Maria Reina-Bueno2

Mercedes Gómez-Castro3

Pedro V. Munuera-Martínez2

1Patricia Granados Podología. Sevilla, Spain

2Departamento de Podología. Universidad de Sevilla, España

3Junta de Andalucía. Sevilla, Spain

Abstract

Introduction: The aim of this study was to analyze whether there is a difference in first ray mobility between individuals with and without low back pain, mobility could be related to the presence of low back pain.

Patients and methods: A cross-sectional observational study was conducted with 400 adults aged 18 to 65. Dorsiflexion, plantarflexion, and total mobility of the first ray were measured using a validated instrument. Feet were classified as normal or non-normal based on clinical criteria, and low back pain was assessed using a visual analog scale.

Results: No clinically relevant differences in first ray mobility were found between individuals with and without low back pain overall. However, when comparing normal feet without low back pain to with altered mobility and with low back pain, a significant reduction in plantarflexion was observed (mean: 6.4 mm vs. 5.1 mm), suggesting a possible link between reduced first ray mobility and low back pain.

Conclusions: Reduced plantarflexion of the first ray may be associated with the presence of low back pain. This finding highlighted the importance of considering foot biomechanics in the comprehensive management of lumbar pain and suggested the need for further research to confirm this relationship.

Keywords: First ray, foot, plantar flexion, dorsal flexion, total mobility, low back pain

Resumen

Introducción: El objetivo del estudio fue analizar si existe una diferencia en la movilidad del primer radio del pie entre personas con y sin dolor lumbar, y si dicha movilidad pudiera estar relacionada con la presencia de lumbalgia.

Pacientes y métodos: Se realizó un estudio observacional transversal con 400 adultos entre 18 y 65 años. Se evaluó la dorsiflexión, la plantarflexión y la movilidad total del primer radio mediante un instrumento validado. Se clasificaron los pies como normales o con movilidad alterada según criterios clínicos y se registró la presencia de dolor lumbar mediante escala visual analógica.

Resultados: No se encontraron diferencias clínicamente relevantes en la movilidad del primer radio entre personas con y sin lumbalgia en general. Sin embargo, al comparar pies normales sin lumbalgia con pies con movilidad alterada y con lumbalgia, se observó una disminución significativa en la plantarflexión (media: 6.4 mm vs. 5.1 mm), lo que sugiere una posible relación entre la movilidad reducida del primer radio y el dolor lumbar.

Conclusiones: La disminución de la plantarflexión del primer radio podría estar asociada con la presencia de lumbalgia. Este hallazgo destacó la importancia de considerar la biomecánica del pie en el abordaje integral del dolor lumbar y sugirió la necesidad de futuras investigaciones para confirmar esta relación.

Palabras claves: Primer radio, pie, plantarflexión, dorsiflexión, movilidad total, dolor lumbar

Corresponding autor

María Reina Bueno

mreina1@us.es

Received: 30-06-2025

Accepted: 22-07-2025

Introduction

The first ray of the foot—comprising the first metatarsal and the medial cuneiform—is essential for foot stability and normal gait development, especially during stance and propulsion(1,2). Dysfunction has been linked to hallux valgus (HV) (3), hallux limitus (HL), hallux rigidus (HR)4 and even low back pain(5).

The joints involved in first-ray motion are the first cuneometatarsal joint and the medial cuneonavicular joint. Their motion occurs about a common axis(6) directed from posterior–medial–dorsal to anterior–lateral–plantar, angled ~45° to the frontal and sagittal planes and slightly to the transverse plane. Because transverse-plane motion is negligible, sagittal- and frontal-plane movements are most relevant, producing dorsiflexion–inversion and plantarflexion–eversion(1).

Certain foot biomechanical alterations, such as limited motion of the first metatarsophalangeal joint, can produce proximal compensations that affect posture and gait dynamics. These compensations may contribute to lumbar discomfort, in part through overuse of muscle groups such as the iliopsoas(5). Despite biomechanical plausibility and frequent clinical observation, no studies were identified that specifically analyze the relationship between first-ray mobility and low back pain in adults.

Understanding how foot biomechanics influences adjacent pathologies, such as low back pain, is key to comprehensive management of musculoskeletal pain. First-ray mobility affects gait; when restricted, it may alter hip and spinal motion. Studying this relationship could improve diagnosis and enable foot-centered therapies. The paucity of prior studies justifies this investigation.

In 2020, Munuera-Martínez et al. (7) validated a new first-ray mobility meter that is light, portable, simple, and suitable for daily clinical useAlthough valid and reliable—and used in prior studies(7,8)—no studies have related first-ray mobility measured with this device to low back pain. Therefore, our objective was to determine whether first-ray motion, measured with this instrument, differs between individuals with and without low back pain.

Patients and methods

Participants

We conducted a cross-sectional observational study. Measurements were obtained between November 2020 and June 2023. The target population was adults aged >18 and < 65 years who attended the Clinical Area of Podiatry at the University of Seville and other private clinics in Seville.

Inclusion criteria were healthy adult men and women aged >18 and < 65 years. To compare first-ray mobility in people with and without low back pain, we included participants without lumbar pathology or pain and participants with nonspecific low back pain not attributable to a specific diagnosis at that level. Exclusion criteria were prior surgery on the first ray; fractures of the feet or lower limbs; systemic disease affecting foot morphology (eg, rheumatoid arthritis, Charcot foot); and dementia, expressive difficulties, or mobility limitations.

Procedure

A sociodemographic and health history form was completed for each participant. Foot examination quantified dorsiflexion of the first metatarsophalangeal joint (first MTPJ), ankle dorsiflexion, and first-ray dorsiflexion (DF), plantarflexion (PF), and total mobility. All measurements were performed by the same examiner with >7 years’ experience in foot assessment.

The Foot Posture Index (FPI) was recorded and later used to classify feet as neutral, pronated, or supinated?. Feet were considered normal if, in addition to meeting Kirby’s normality criteria(10), they demonstrated first MTPJ dorsiflexion > 50° and an FPI score between +1 and +5 (neutral).

Low back pain was assessed with a visual analog scale (VAS) (11,12).

First-ray mobility was measured with the Medidor de Primer Radio® (Fresco Podología SL, Barcelona, Spain), a valid, reliable instrument used in previous studies (Figure 1) (7,8,13). For the measurement, one hand maintained the horizontal arm over the heads of the 2nd–5th metatarsals while the other hand positioned the opposite horizontal arm vs the head of the 1st metatarsal. From this position, the 1st metatarsal head and horizontal arm were moved upward to read dorsiflexion (mm) on the vertical arm and downward to read plantarflexion (Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4) (7,8). Each foot was measured three times; the mean was used for analysis.

Data Analysis

Sample size was calculated using simple random sampling for estimation of a mean in infinite populations, assuming a 5 % relative sampling error (coefficient of variation) and a 95 % confidence level, with estimators derived from a 20-person pilot. The result was 393 participants; 400 were ultimately included to account for potential data losses.

Descriptive statistics included absolute (N) and relative (%) frequencies, means, standard deviations (SD), and 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles (interquartile range).

For intraobserver reliability, in a random subset of 40 feet (20 right, 20 left), dorsiflexion and plantarflexion were remeasured by the same investigator after 15 days. Agreement was assessed with a 2-way mixed-effects intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC).

Normality of quantitative variables was tested with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov statistic. Group differences were assessed with independent-samples t tests when normality held or the Mann–Whitney U test otherwise. Effect size was calculated with Cohen d or Rosenthal r and interpreted as < 0.2 none, 0.2–0.5 small, 0.5–0.8 medium, and ≥ 0.8 large.

A 2-step cluster analysis using silhouette measures of cohesion and separation was performed to evaluate cluster quality (good, fair, poor).

Analyses were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics (27).

Results

We enrolled 400 subjects (331 women, 69 men). Mean age was 42.2 ± 1.1 years. Mean BMI was 24.7 ± 4.4 kg/m². ICCs showed excellent repeatability for all first-ray mobility variables (right-foot DF ICC, 0.979; right-foot PF ICC, 0.931; left-foot DF ICC, 0.998; left-foot PF ICC, 0.973).

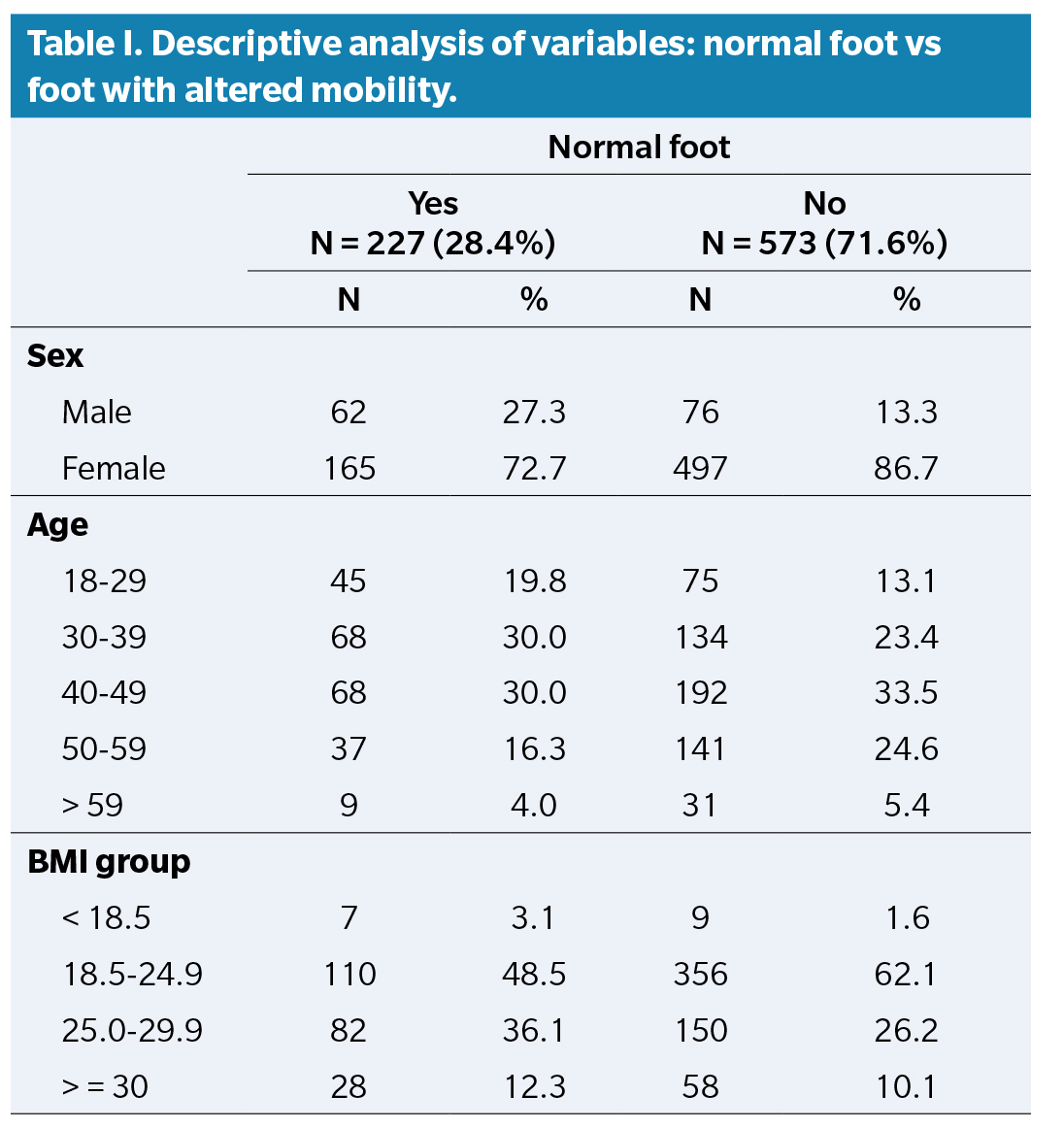

Because one person may present one normal foot and one abnormal foot, analyses of first-ray mobility were conducted by foot. Of 800 feet, 227 were normal and 573 had altered mobility. Descriptive results for measured variables are shown in Table 1. Low back pain was present in 188 individuals (47 %); mean VAS was 4.2 ± 3.1 mm (median, 5; IQR, 1.0-7.0). FPI classifications for the right foot were 333 neutral, 42 pronated, and 25 supinated; for the left foot, 332 neutral, 43 pronated, and 25 supinated. First MTPJ extension measured 60 ± 8.4° on the right and 63 ± 9.3° on the left.

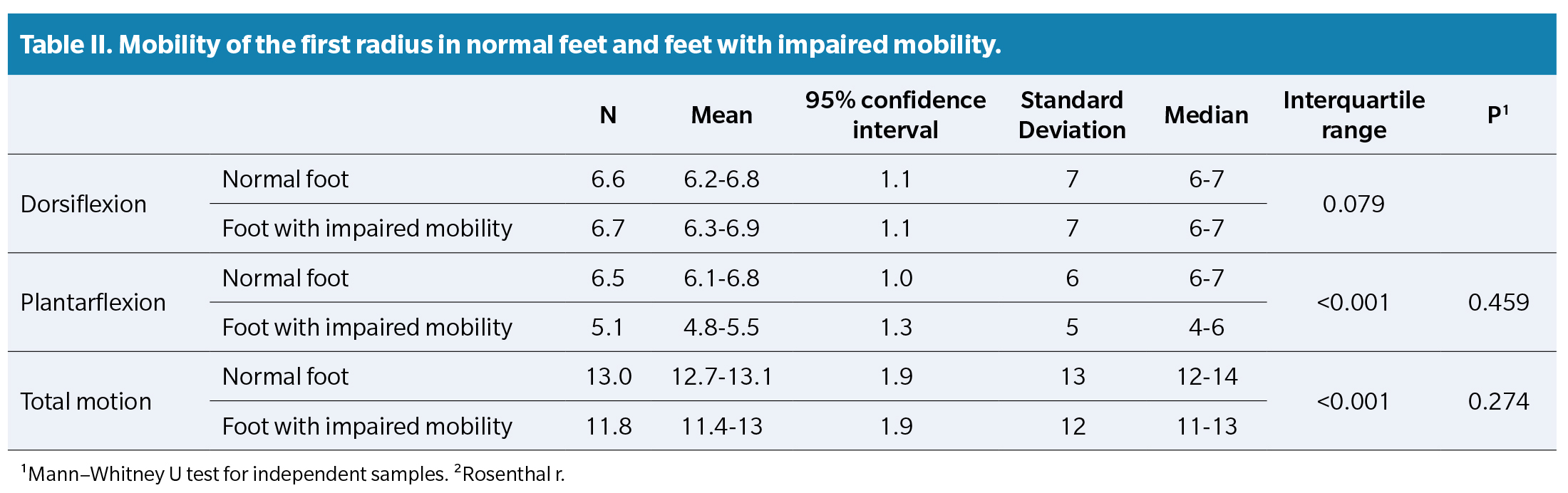

Table 2 shows differences in first-ray mobility variables between normal and altered-mobility feet.

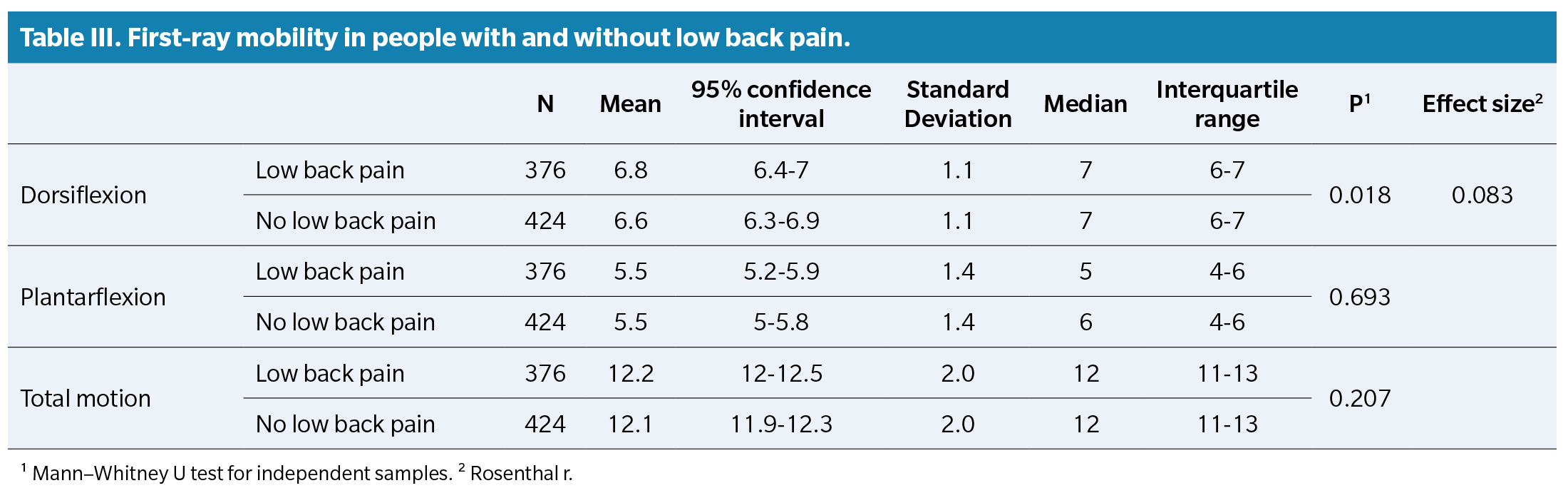

Two-step clustering was used to define DF, PF, and total mobility (TM) ranges for normal vs non-normal feet. DF ranged 6-7 mm in both groups. PF ranged 6-7 mm in normal feet and 4-6 mm in altered-mobility feet. As shown in Table 3, no significant differences were observed in first-ray mobility between individuals with vs without low back pain. Although DF was slightly lower in those without low back pain, medians were identical and effect size was very small, so this difference is unlikely clinically relevant.

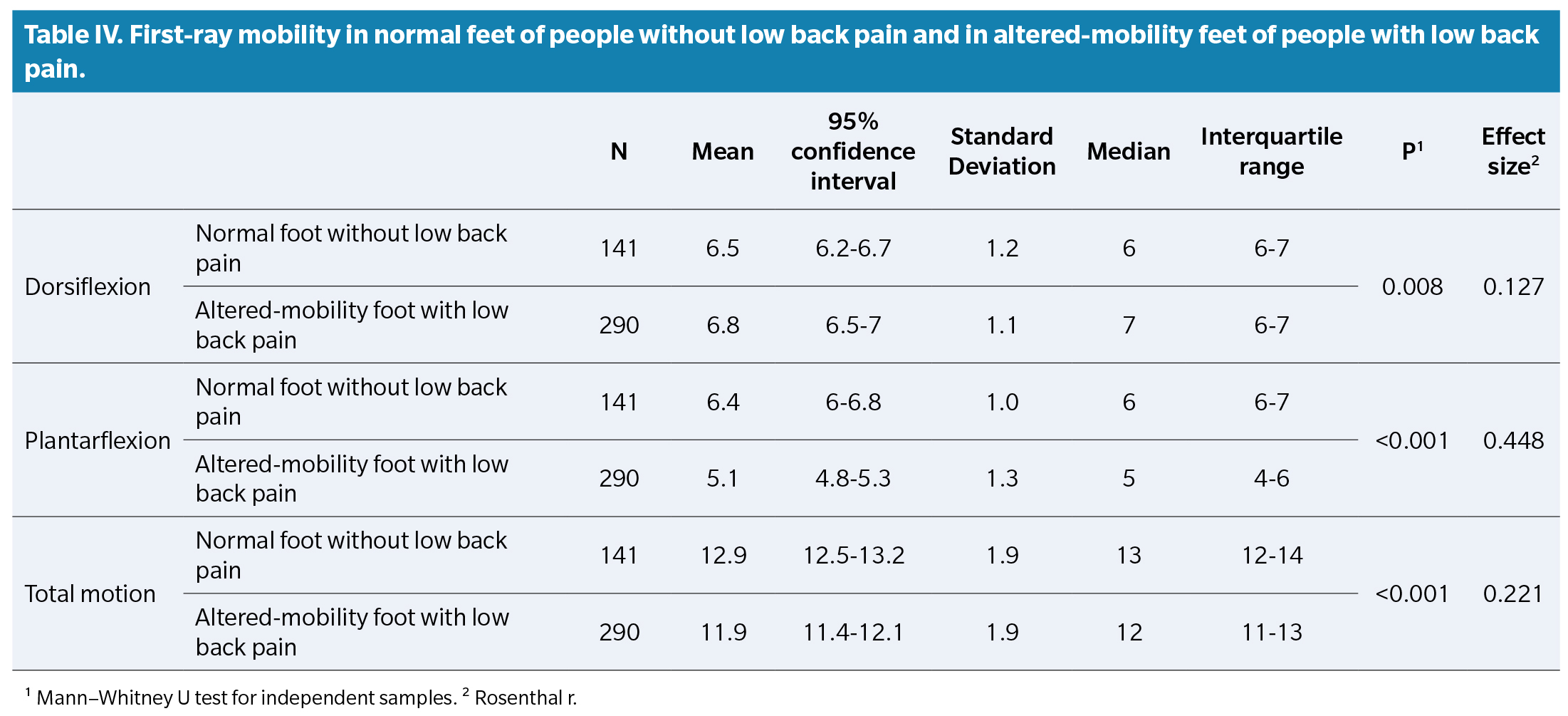

However, when filtering to pain-free participants with normal feet and comparing their first-ray mobility with participants with low back pain and altered-mobility feet, PF showed the largest effect size (though not large by convention) and was lower in the low-back-pain group (Table 4). Thus, while differences were statistically significant, they should be interpreted cautiously in clinical terms.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to determine whether first-ray motion measured with the Munuera-Martínez device(7) differs between individuals with and without low back pain. In our study, plantarflexion was reduced in cases with low back pain.

Throughout the years, numerous investigations have established a functional relationship between anatomically distant regions—the foot and the lumbar spine. Distal foot support alterations may promote nonspecific low back pain. Low back pain affects up to 80 % of people at some point(14,15). The foot’s influence is linked to functional changes that certain pedal alterations induce in the lumbopelvic musculoskeletal system.

Foot dysfunction can alter pelvic biomechanics and, in turn, the lumbar spine(16,17). Abnormal rearfoot pronation alters foot support during gait, changing pelvic position and mobility and increasing lumbar pathology risk(18,19,20,21,22) Reported effects of abnormal pronation include increased anterior and lateral pelvic tilt(23,24), lateral tilt and axial rotation of the thorax in unilateral hyperpronation(25), alterations in lumbopelvic muscle function(26,27,28)and increased lumbar lordosis and thoracic kyphosis(29). Recent studies also show that flatfoot—typically associated with abnormal pronation—is an independent risk factor for lumbar degenerative disease(30), including intervertebral disc herniation(31).

A biomechanical foot dysfunction such as limited first-ray mobility can change gait and global posture because this joint is the pivot for whole-body advancement during the propulsive phase. Repeated thousands of times daily over long periods, restricted motion can alter whole-body and foot biomechanics. If first-ray motion is impaired, the kinetic energy for this motion must dissipate elsewhere, creating a specific compensation pattern. Postural changes and symptoms can include low back pain. Dananberg (1993) (5,32) proposed that limiting first-ray dorsiflexion or plantarflexion impedes full development of the propulsive phase. The body then compensates with greater ankle dorsiflexion and increased knee and hip flexion, shortening step length and creating imbalance between hip flexors and extensors. The quadratus lumborum and iliopsoas compensate by increasing pelvic rotation, potentially producing low back pain. Our study observed an association between reduced first-ray plantarflexion and low back pain.

A 2013 systematic review by O’Leary et al. (22) indicated that biomechanical alterations may cause chronic low back pain, relating flatfoot, ankle instability, sagittal-plane block, and excessive pronation to low back pain. Barwick et al. (33) also reviewed the literature and suggested that lumbopelvic-hip muscle dysfunction is involved in lower-limb functional changes and is strongly related to conditions traditionally attributed to excessive foot pronation during gait.

Conversely, Kendall et al. (34) argued that evidence linking low back pain and foot behavior—specifically excessive pronation—is insufficient to be definitive. Yazdani et al. (17) (2018) concluded that ground-reaction forces and impulses across plantar regions are affected by low back pain.

Anukoolkarn et al. (35) (2015) examined patterns of plantar pressure distribution during the mid-stance phase of gait in subjects with chronic low back pain and asymptomatic controls. Forty subjects with chronic low back pain and 40 asymptomatic subjects participated. They found that the mean peak pressure distribution patterns differed between the chronic low back pain group and asymptomatic subjects, indicating that plantar surface pressures were unevenly distributed in those with chronic low back pain during mid-stance. Lee et al. (36) (2011) investigated changes in plantar pressure distribution during gait in 30 individuals with low back pain and 30 without. Patients with low back pain walked with a shorter anteroposterior excursion of the center of pressure, possibly as a compensatory pain-avoidance action. The plantar pressure distributions in those with low back pain provided evidence of altered gait patterns. Although these studies do not specifically address the relationship between first-ray mobility and low back pain, first-ray mobility is related to plantar pressure distribution, suggesting a potential connection between first-ray mobility and low back pain.

Consistent with our findings, individuals with low back pain showed less first-ray plantarflexion. First-ray plantarflexion is essential for normal propulsion. When absent, the foot may compensate with delayed pronation to facilitate ground contact of the first metatarsal head(37). Excessive pronation during gait has been repeatedly linked to low back pain. Excessive pronation induces altered alignment of the tibia, femur, pelvis, and lumbar spine, provoking pain. Excessive pronation produces internal rotation of the medial malleolus and, consequently, internal rotation of the femur and tibia, inducing ipsilateral pelvic tilt and lumbar vertebral rotation during gait—altering whole-body kinetics and potentially causing low back pain. Because abnormal pronation relates to altered first-ray mobility, this alteration would also relate to low back pain. Moreover, weakness of lower paraspinal/postural muscles and low back pain have been linked to limited ankle range of motion, complicating causal direction. What can be concluded is that abnormal lower-extremity biomechanics are associated with functional/mechanical low back pain (25,38,39,40,41).

This study provides evidence of a possible association between first-ray mobility and low back pain, highlighting a significant reduction in plantarflexion among subjects with low back pain and altered foot mobility. This finding supports the hypothesis that foot biomechanical alterations can have upstream effects on lumbar posture and function. Strengths include a validated measurement methodology, adequate sample size, and detailed statistical analysis.

Limitations include geographic restriction of the sample and exclusion of individuals < 18 years, limiting generalizability. The sample was predominantly female (82.75 %), which may influence results and limit applicability to men. The cross-sectional design precludes causal inference between first-ray mobility and low back pain. Potential confounders—BMI, physical activity level, other joint disorders, sedentary behavior—were not considered, though they may influence both foot mobility and low back pain.

Given the association between reduced first-ray plantarflexion and low back pain, clinical practice should systematically include biomechanical foot evaluation—particularly of the first ray—in patients with nonspecific low back pain. Such assessment may identify distal contributors to lumbar pain and facilitate a more comprehensive therapeutic approach.

Future research should include longitudinal studies to establish causal relationships between first-ray mobility and the course of low back pain, and clinical trials evaluating the effect of customized foot orthoses on low back pain.

In conclusion, reduced first-ray plantarflexion may be associated with low back pain. Our findings suggest the need to study plantarflexion in greater depth because its reduction is significant and may be related to back pain.

Ethics declaration

All participants provided written informed consent after being informed about study characteristics and volunteered to participate. The study was approved by Universidad de Sevilla (Seville, Spain) Research Ethics Committee (internal code 2244-N-19) and conducted in full compliance with the criteria set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki

Conflict of interest

None

Funding

None

Contributions of the authors

Study conception and design: MRB, PVMM. Data collection: PGG, MGC, PVMM. Analysis and interpretation of results: PGG, MRB, MGC. Creation, writing and preparation of the initial draft: PGG, MRB, MGC, PVMM. Final review: PGG, MRB, MGC, PVMM

References