doi.org/10.20986/revesppod.2025.1733/2025

ORIGINAL

Influence of climbing-shoe size on the podiatric conditions of the climber’s foot: an observational study

Influencia del tamaño de los “pies de gato” en las condiciones podológicas del pie del escalador. Estudio observacional

Paula Cobos Moreno1

Alvaro Astasio Picado2

Sandra Iglesias Garcia2

Beatriz Gómez-Martín1

1Universidad de Extremadura. Cáceres, España

2Universidad de Castilla La Mancha. Toledo, España

Abstract

Introduction: Climbing is a multidisciplinary sport whose main objective is to reach the highest point of a rock face or complete a route. Climbing has become very popular in recent years, leading to a proportional increase in injuries. Most foot injuries in climbing are the result of using climbing shoes that are unnatural in shape or do not fit well. The reduction in the foot’s internal capacity forces it to compress inside the shoe. The main objective is to observe if there is a relationship between the size of the “climbing shoe” in the practice of climbing and the appearance of injuries derived from its use in the feet.

Patients and methods: The study population consisted of fifty-three climbers (32 men and 21 women) belonging to the FEXME (Extremaduran Mountain and Climbing Federation). The diagnosis was based on the identification of clinical signs and symptoms determined by two previously trained examiners, in order to minimize bias between examiners.

Results: Seventy percent of the climbers used shoes shorter than their feet, with a significant difference between foot length and shoe length. When relating the number of years of climbing experience with the occurrence of injuries, a significant difference was also observed (p-value < 0.05), the most common injuries were HAV, Hallux Limitus, Hyperkeratosis, representing 60 % with such injuries.

Conclusion: In conclusion, climbers use climbing shoes that are smaller than their usual foot size, and the longer they have been practicing this sport, the greater the likelihood of suffering some type of foot injury.

Keywords: Foot, footwear, shoes, size, sport, climbing shoes, climbing

Resumen

Introducción: La escalada es un deporte multidisciplinar cuyo objetivo principal es alcanzar el punto más alto de una pared rocosa o completar una vía. Su creciente popularidad en los últimos años ha conllevado un aumento proporcional de las lesiones. La mayoría de las lesiones del pie en escalada se relacionan con el uso de “pies de gato” de forma o talla no natural para el pie. La reducción de la capacidad interna del calzado fuerza la compresión del pie en su interior. El objetivo principal fue observar si existe relación entre la talla del pie de gato y la aparición de lesiones en los pies derivadas de su uso.

Pacientes y métodos: La población de estudio consistió en: 53 escaladores (32 hombres y 21 mujeres) pertenecientes a la FEXME (Federación Extremeña de Montaña y Escalada). El diagnóstico se basó en la identificación de signos y síntomas clínicos determinada por dos exploradores previamente entrenados, para minimizar el sesgo interobservador.

Resultados: El 70 % de los escaladores utilizaba un pie de gato más corto que su pie, observándose una diferencia significativa entre la longitud del pie y la del calzado. Al relacionar los años de experiencia con la aparición de lesiones, también se observó una diferencia significativa (p < 0.05); las más frecuentes fueron HAV, hallux limitus e hiperqueratosis, responsables todas estas patologías del 60 % de las lesiones.

Conclusión: Los escaladores tienden a usar pies de gato más pequeños que su talla habitual y, cuanto mayor es el tiempo practicando este deporte, mayor es la probabilidad de presentar alguna lesión en el pie.

Palabras clave: Pie, calzado, zapatos, talla, deporte, pies de gato, escalada

Corresponding author

Paula Cobos Moreno

pacobosm@unex.es

Received: 21-04-2025

Accepted: 08-07-2025

Introduction

Climbing is a multidisciplinary sport whose main objective is to reach the highest point of a rock face or to reach the end of an established route(1,2). Different types of climbing can be distinguished(3,4): sport climbing and traditional climbing, in which the climber reaches the “top” of the route and then descends. In sport climbing, fixed anchors must be used, while in traditional climbing, the climber must protect themselves from falling by fixing the anchors to the rock themselves(1,2,3). Sport climbing, in particular, has become very popular in recent years, with an exponential increase in the number of practitioners. This popularity may be due to factors such as the increase in competitions or the inclusion of climbing as an Olympic sport in the Tokyo Games (2020) (4).

In any case, the increase in competitions leads to a proportional increase in injuries resulting from the practice of the sport. The causes of these injuries include intrinsic risk factors (specific to each individual) and extrinsic factors, such as poor technique, the use of inappropriate equipment or misuse of equipment, and/or a lack of knowledge about the appropriate choice of sports footwear in the case of foot injuries(5,6).

Climbing involves a series of acyclic movements that seek to move the body, actively involving both the hands and feet. As for the movements of the lower body, there are different technical gestures whose main objective is to bring the center of gravity closer to the wall. One such movement is the heel hook, which involves placing the heel on a foothold. In contrast, the “toe hook” movement involves applying pressure against a foothold using the back of the foot. To accompany this sporting movement, special technical footwear called “climbing shoes” is required(6,7). Cat’s paws are specialized technical footwear for climbing, i.e., shoes designed for climbing walls, whether on natural rock or in indoor facilities such as climbing walls. They have a special design and characteristics for this purpose(7. They are very light, flexible, and grippy, thanks to the special adhesive rubber on the sole, side bands, and front, which provides greater grip and precision. Initially, they were made of leather, but over the years and with industrial advances, different technical materials have been used that give them other or better characteristics than leather. However, this material continues to have its fans due to its price, durability, and adaptability. Attributes such as the concave shape that exerts pressure on the toes and the asymmetry that concentrates pressure on the big toe are basic elements of modern climbing shoes (Figure 1) (7,8).

Most foot injuries in climbing are the result of climbing shoes with an unnatural shape or an inadequate size. The reduction in the internal capacity of the foot forces the foot to compress inside the shoe, with a consequent change in the morphology and normal function of the foot structures8. The foot shortens due to supination and contraction of the plantar structures9. In addition, in the forefoot, the proximal interphalangeal joints and, in most cases, the distal joints also flex, and the metatarsophalangeal joints hyperextend, resulting in a claw position of the toes(8,9,10).

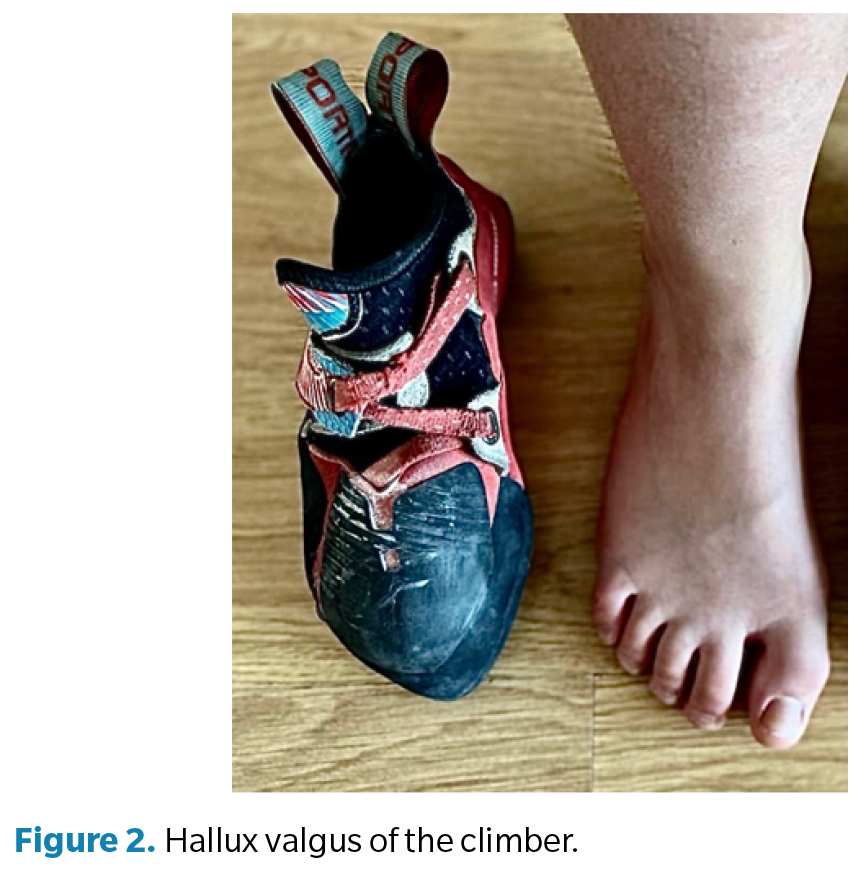

The existing literature on climbers’ feet has established that most athletes have experienced some type of pain or deformity while practicing this sport, either in the foot itself or even in the Ankle(10,11,12). The most common injuries and deformities in climbers’ feet are toe deformities: hallux limitus, subungual hematoma, and hallux valgus (Figure 2) (11). Although well-fitting climbing shoes help biomechanically to prevent chronic foot disorders, it is important to pay special attention to the size of the “climbing shoe” in relation to the climber’s foot. The aim of the design of climbing shoes is to achieve a perfect fit to the foot, like a second skin. In most cases, to achieve this fit, climbers accept pain during and after climbing(10,11,12). Studies have found that climbers use poorly fitting and tight climbing shoes, even wearing shoes four sizes smaller than their actual foot size(10).

Recent publications describe foot alterations directly related to the use of climbing shoes. Traumatic injuries are the most common(11,12,13,14,15). The main objective of this research is based on this premise, starting from the observation of the relationship between the size of climbing shoes in the sport of climbing and the subsequent appearance of injuries resulting from their use on the feet.

Patients and methods

Study design and population

A descriptive, cross-sectional, prospective study was carried out. The participants were regular climbers at the Cerzawall climbing wall in Plasencia (Extremadura, Spain) and were members of the FEXME (Extremadura Mountain and Climbing Federation).

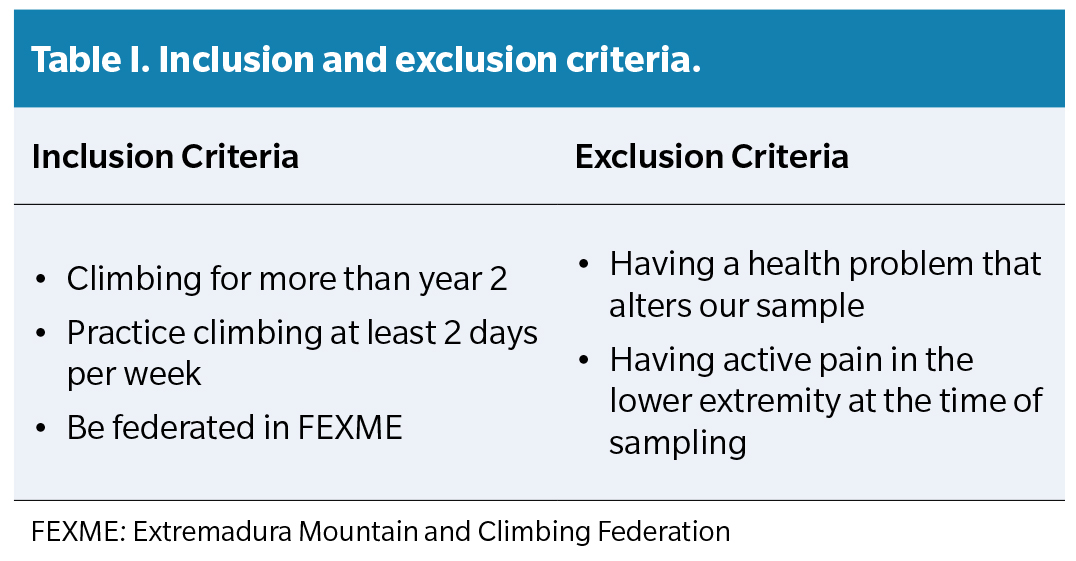

Screening surveys were conducted among volunteer users of the climbing wall in order to obtain a random sample, sample coded by number and take the patients’ numbers randomly. After the surveys were completed, inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied to the entire participating population to determine the final members of the study and thus obtain the sample to be analyzed (Table 1).

Outcomes

A physical and diagnostic examination was carried out using clinical tests, such as measuring the length and width of the respondents’ feet and their footwear. In addition, the variables collected through the initial questionnaire were recorded, such as age, sex, years of climbing experience, and the size and model of climbing shoes. On the other hand, the inspection variables detected in the clinical examination were included: morphostructural alterations (hallux valgus, hallux limitus, claw toes), dermatological alterations (blisters, nail problems, hyperkeratotic patterns, hematomas), and nail alterations.

The diagnosis is based on the identification of clinical signs and symptoms determined by two previously trained examiners in order to minimize examiner bias(16). Measurements were taken before climbing. Quantitative variables such as the length and width of the climber’s foot and footwear were measured with a tape measure, see Figure 3. The length of the footwear was measured on the outside. On the other hand, measurements of the joint amplitude of the first interphalangeal joint of the first toe were taken with a goniometer, see Figure 4. All measurements were taken by both examiners in triplicate in order to obtain the arithmetic mean of these records and thus minimize intra-examiner bias(17).

Statistical analysis

The SPSS version 21.0 for iOS® software was used for statistical analysis. Qualitative variables were described as simple frequencies and quantitative variables were described with means and standard deviations. Contrast hypothesis testing was performed using 5 % (p < 0.05) as cut-off value for rejecting null hypothesis. it was verified that the study data did not follow a normal model (p value lower than 0.05; Kolmogorov-Smirnov test), so non- parametric statistical tests (Wilcoxon signed-rank test, the Friedman test, and the Mann-Whitney U test) were chosen for quantitavie variables and chi-square test for qualitative variables.

Results

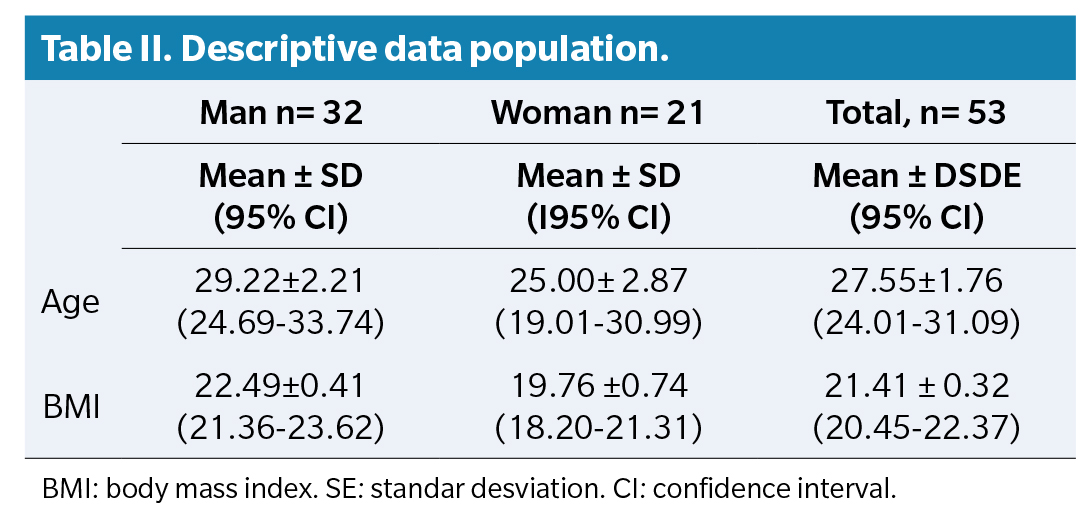

The study population consisted of fifty-three climbers (n = 53): 32 men and 21 women, with a mean age of 27.5 ± 1.76 and a body mass index of 21.41 ± 0.32 (Table 2).

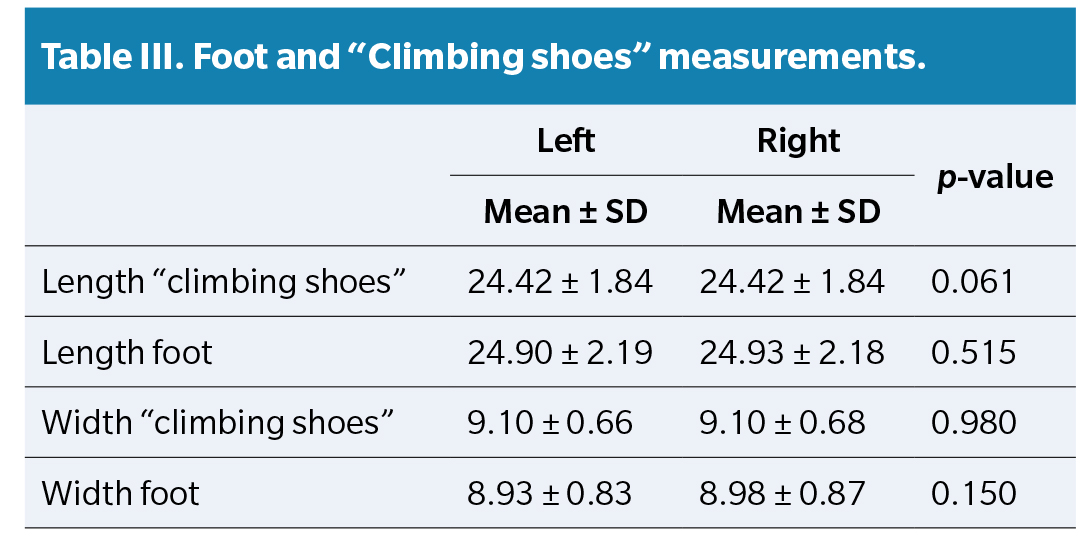

The length of the right shoe compared to the left shoe, as well as the length of both feet, did not show a significant difference (p-value >0.05; Wilcoxon signed-rank test), meaning that both feet and both paws of the cats behave in the same way (Table 3).

Almost 70 % of climbers have a cat length shorter than their foot length (which is the same number of small “cat paws”), with a significant difference between foot length and cat length (p-value 0.010; Wilcoxon signed-rank test), with a difference of almost two sizes between foot size and “cat paw” size.

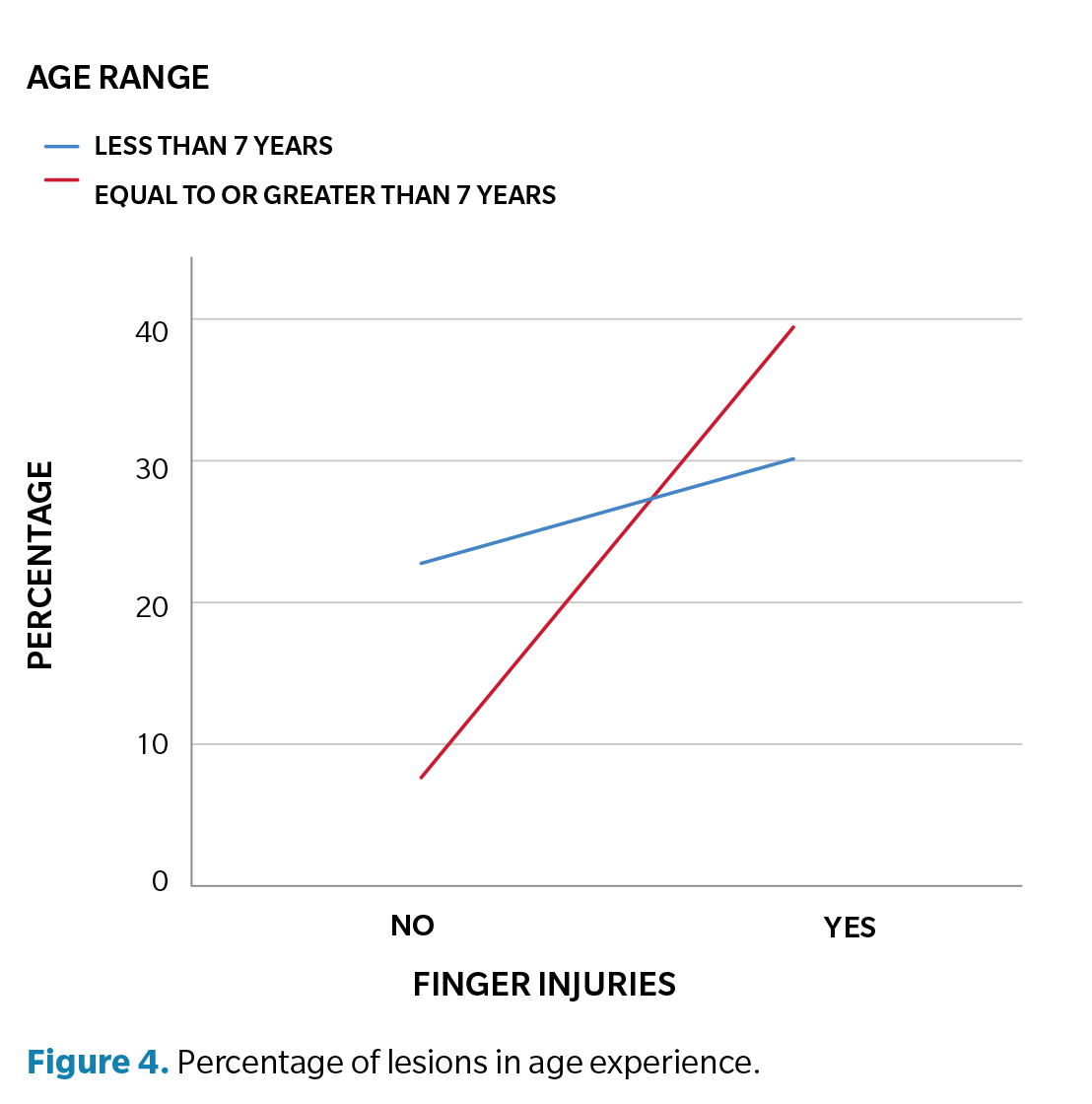

When correlating the years of climbing experience and the occurrence of injuries, a significant difference was also observed (p-value <0.05; Wilcoxon signed-rank test), with a higher incidence of injuries the longer the person had been climbing, when using small climbing shoes (Figure 4).

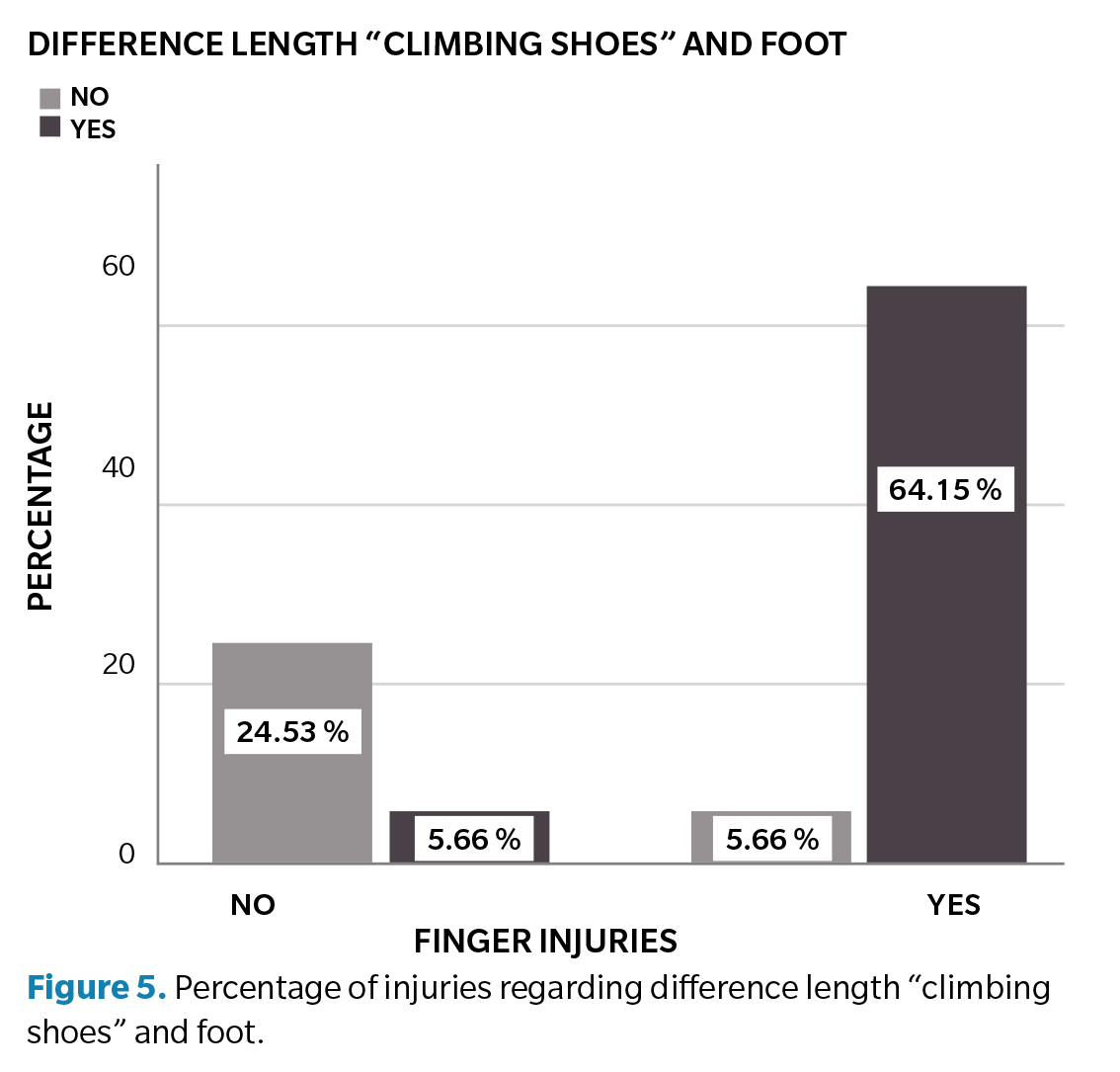

Finally, it was shown that people who use climbing shoes that are too small suffer more injuries than those who use climbing shoes that fit their feet (p-value > 0.05); with the most common injuries being contusions, calluses, HAV, and hallux limitus. Hallux limitus was present in 60 % of the climbers studied (Figure 5).

Discussion

Existing scientific publications on the distribution of injuries between the upper and lower extremities are inconsistent(18) as many of the scientific articles on climbing only present case studies or common injuries to the hands19-22 and are therefore not suitable for analyzing the distribution of injuries. Largiadèr et al(23) found in a study of 332 climbers that 34.4 % suffered injuries and that 34.6 % of these were foot injuries(23). Another recent study on rock climbing injuries states that, of all injuries suffered by climbers and resulting from the practice of this sport, 50 % are traumatic injuries affecting the lower extremities (foot, toes, and ankle), while the upper extremities account for 36 % of all injuries(24). In addition to acute lower limb injuries, the incidence of chronic foot problems increases at higher levels of sport climbing(25,26,27).

Most climbing-related foot injuries are due to the use of unnatural shaped climbing shoes or(7,8)shoes that are too small. Plantar flexion of the metatarsal heads causes a tightening of the plantar fascia(8,9). High-performance athletes who practice climbing suffer more foot deformities and injuries than lower-performance climbers due to the habitual practice of using climbing shoes that are smaller than normal street shoe sizes1(12,13). Authors such as Schöffl have already reported an average difference of two centimeters between the length of the climber’s foot and the length of the “climbing shoe” normally used(20). In addition, between 80 and 90 % of climbers reported foot pain during sports practice associated with the use of “climbing shoes.” However, they accept this discomfort in order to improve their performance(28).

The length of the “climbing foot” and the climber’s foot were measured using the international metric system, both expressed in centimeters (cm). It should be noted that a poor fit or looseness of the footwear in relation to the climber’s foot can cause a failure to adhere to the surface being climbed. However, it is also necessary to control other factors that influence adhesion and that are not so much related to the fit of the climbing shoes to the foot, such as the material of manufacture, the design, and/or their shape(24,25)All of this not only influences the fit, but also the adhesion to the wall during climbing and, therefore, a good choice determines the success of the sporting gesture.

This study shows that 70 % of climbers use climbing shoes that are smaller than the size they would normally wear in everyday footwear. The results are therefore consistent with previous studies, such as that conducted by McHenry in 2015. However, this author measured foot and shoe dimensions based on shoe size(10). Regardless of the measurement tool used to determine foot or shoe length (whether shoe size or the universal metric: centimeters), we can say that the footwear commonly used for climbing (“climbing shoes”) is mostly used with dimensions well below those recommended for footwear that is suitable for the proper morphological and functional development of the foot(10). In addition, it is important to mention the difference between the inner and outer length of the shoe. While external dimensions are easy to measure and quantify, the same is not true for internal dimensions (which are smaller and more difficult to quantify and measure). Therefore, it must be taken into account that the internal capacity of the climbing shoe that will house the climber’s foot will be even smaller than the metric measurement that can be obtained from the outside of the shoe(10,11,12,20).

A poor fit between the size of the shoe and the climbing shoe itself causes very harmful pressure on certain areas of the foot (especially the front). The modern design of climbing shoes means that they tend to have a narrow, asymmetrical toe, which predisposes the toes to problems, causing extension of the metatarsophalangeal joints and flexion of the interphalangeal joints. The most common injuries are calluses, nail bed infections, pressure marks, neurological disorders, and subungual hematomas(11,14,21). In the long term, wearing tight climbing shoes can lead to the development of hallux valgus or hallux limitus deformities(24,25,26,27,28). The results of this study are consistent with previous publications that affirm the direct relationship between the age at which climbing sports are practiced and the appearance of forefoot disorders due to poorly fitting climbing shoes.

In conclusion, results of the present study help to confirm that climbers use climbing shoes that are smaller than their usual foot size. The small size of the climbing footwear used progressively and continuously (70 % of the study population) is the cause of foot deformities in climbers. Furthermore, it should be noted that the longer the number of years of practice of the sport, the greater the likelihood of some type of foot injury, bearing in mind that the most common injury is hallux limitus.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to the University Podiatry Clinic of the University of Extremadura, which has generously provided its facilities and equipment for this study. We would also like to thank the CerezaWall climbing Center for allowing us to use its facilities and access its athletes

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest

Funding

This research has not received external funding

Contributions of the authors

Conception and design: PCM, AAP, SIG, BGM

Data collection: PCM, AAP, SIG, BGM

Analysis and interpretation of results: PCM, AAP, SIG, BGM

Creation, writing and preparation of the draft: PCM, AAP, SIG, BGM

Final review: PCM, AAP, SIG, BGM

Ethics declaration

All subjects signed the informed consent form and voluntarily agreed to participate in this study. This study was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the University of Extremadura (Spain) and was planned and carried out in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. It was approved by the committee on March 3, 2021, with registration number 15/2021

References