doi.org/10.20986/revesppod.2025.1725/2025

CLINICAL CASE

Success of verruca vulgaris curettage combined with 90 % phenol solution. Case report

Eficacia del curetaje en verruga vulgar combinado con solución de fenol al 90 %. A propósito de un caso

Brian Villanueva Sánchez1

1Práctica privada. Barcelon, Spain

Abstract

Warts are skin lesions caused by human papillomavirus. Taking into account on their location and evolution, they can be a challenge to the podiatrist to carry out an effective treatment. This article shows the clinical case of a 63-year-old patient, who presented a recalcitrant wart for more than one year, due to the refractory nature of the wart, the failure of previous conservative and invasive treatments. It was decided to perform a surgical intervention a curettage and the use of phenol solution. The aim of this article is to demonstrate a mixed treatment with positive results against recurrent wart.

Resumen

Las verrugas son lesiones cutáneas causadas por el virus del papiloma humano. Dependiendo de su localización y evolución pueden suponer un reto para el podólogo a la hora de establecer un tratamiento efectivo. El presente artículo muestra el caso clínico de un paciente de 63 años que presentaba una verruga recalcitrante de más de un año de evolución. En este caso debido al carácter refractario de la verruga y al fracaso en los tratamiento conservadores e invasivos previos, se decidió realizar una intervención quirúrgica mediante curetaje y uso de solución de fenol. El objetivo de este artículo es poner en evidencia un tratamiento mixto con resultados favorables frente a una verruga recurrente.

Corresponding author

Brian Villanueva Sánchez

villanueva1brian@gmail.com

Received: 01-02-2025

Accepted: 06-16-2025

Introduction

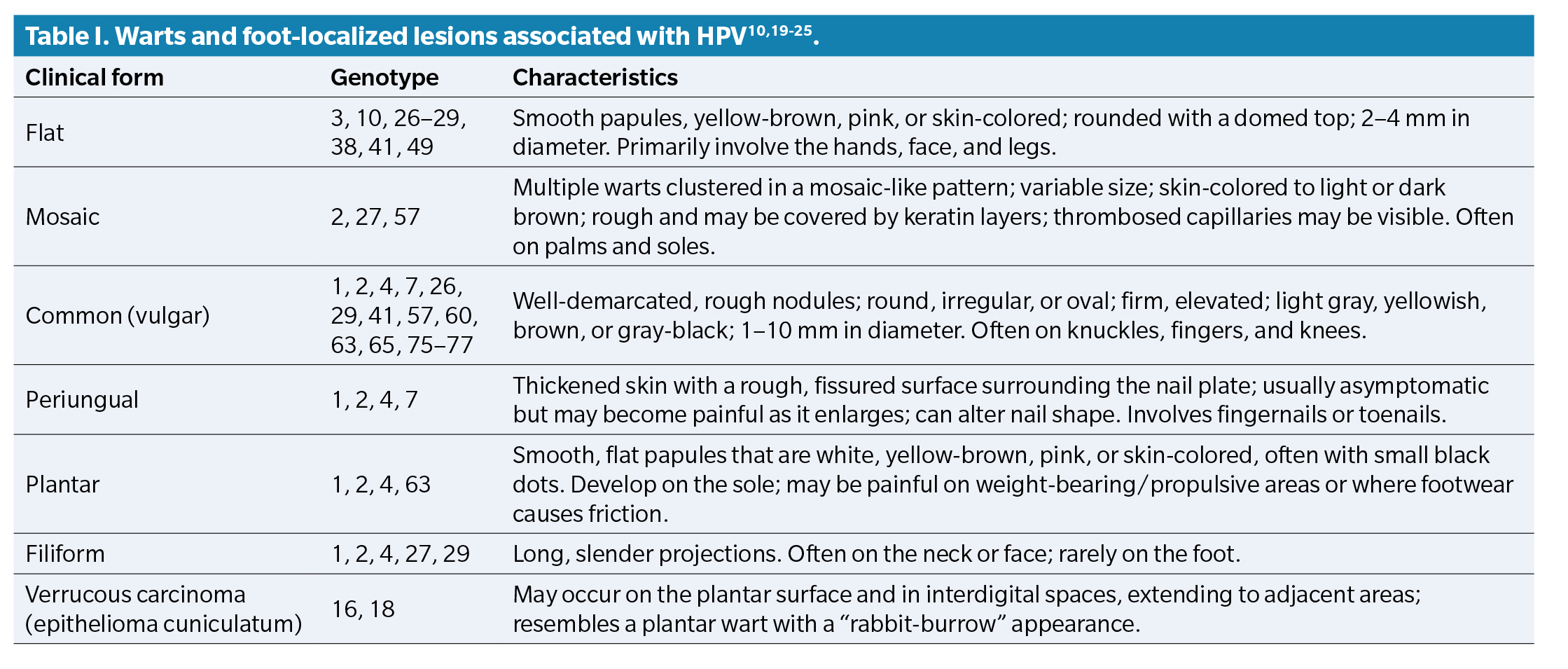

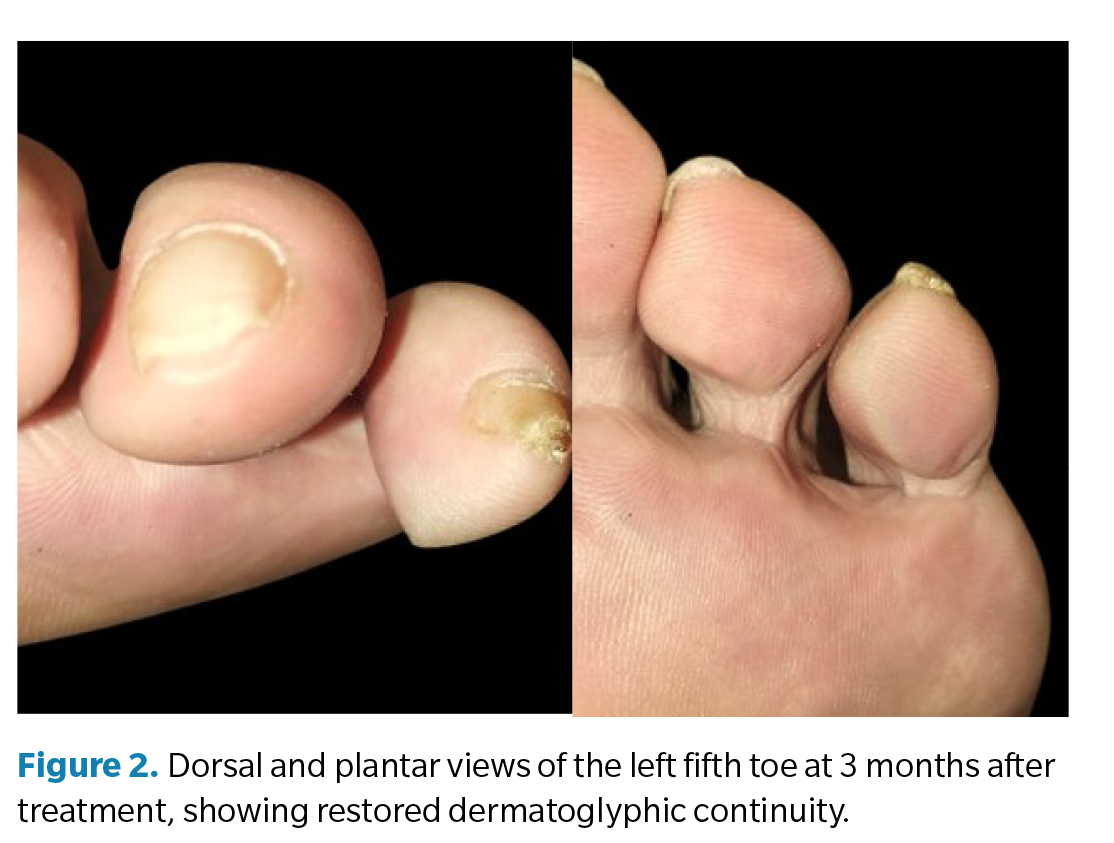

Warts are benign skin lesions caused by human papillomavirus (HPV) (1). They are small, nonenveloped, double-stranded DNA viruses(2). Warts can substantially affect quality of life and may cause serious disease in certain immunocompromised populations. (1)The estimated prevalence of cutaneous warts in the general population is 7-12 %(3). More than 350 HPV genotypes are currently known; of podiatric interest are those affecting the dorsum and sole of the foot, interdigital spaces, digital pulp, eponychium, and hyponychium(3) (Table 1).

HPV infection is linked to tissue damage that proliferates within epithelium, with specific tropism for the epidermis and cutaneous mucosa. Viral persistence reflects multiple immune-evasion mechanisms and the fact that natural antibody formation occurs in only 30-50 % of individuals, is weak and short-lived, and suggests immune ignorance, inadequate immunity, or anergy—fostering long-term infection(5,6). Spontaneous resolution typically occurs within 6 months to 2 years and favors about 40 % of cases(7,8).

Treatment is generally directed at clearance, though in some circumstances it is more appropriate to limit spread or simply relieve symptoms. Management must be individualized, considering wart type, duration, extent, patient age, and immune status. Destructive physical or chemical methods alter infected host cells and may facilitate an immune response to the virus(9). The objective of this report is to highlight for the podiatric community an additional option for warts refractory to noninvasive therapies. This article was prepared in accordance with the CARE (Case Report) clinical practice guidelines(10).

Case report

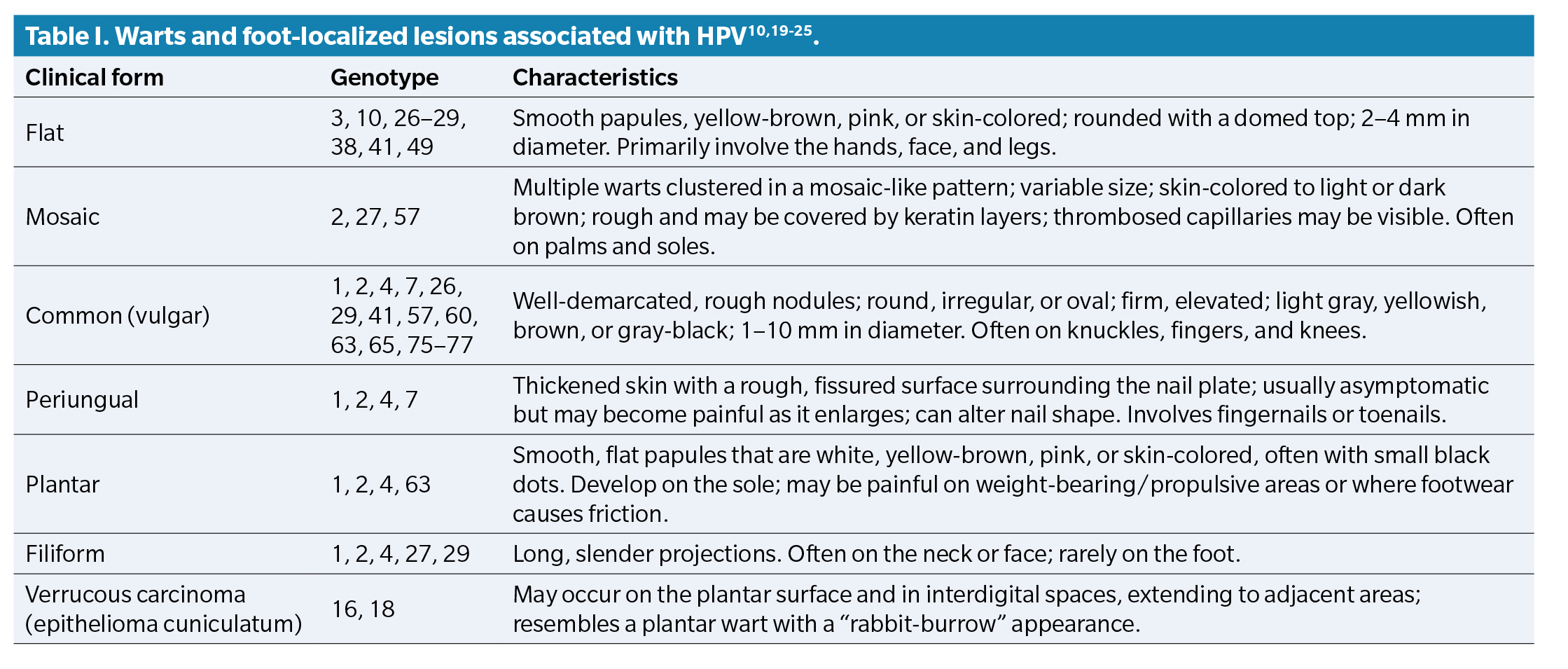

We describe a 63-year-old man presenting with a > 1-year history common wart (CW) that had not responded to conservative treatments (silver nitrate and nitric acid) applied before his first visit to our center. History included dyslipidemia and hypertension, both medically treated. Examination showed a 15 mm × 10 mm CW on the left fifth toe (Figure 1).

Given the wart’s size, we performed the multipuncture–Falknor technique and prescribed oral immunomodulator capsules (Inmunoferon®; Industrial Farmacéutica Cantabria SA, Spain) for 2 months. At the 2-month follow-up, there was no meaningful change (Figure 1: dorsal and plantar views of the left fifth toe, showing a wart with thrombosed capillaries and disrupted dermatoglyphics).

Because of refractoriness, we proceeded with curettage plus 90 % phenol. The ambulatory procedure was done under local anesthesia. With the patient supine, the foot was prepared and draped; a digital block of the fifth toe was performed with 2 % mepivacaine, and hemostasis achieved with an elastic digital tourniquet. The wart’s keratinized surface was pared with a No. 10 blade, and a tissue sample was sent for histopathology. Epidermal curettage was then performed using a Martini curette, enlarging the margins by 2 mm while avoiding the dermis (as warts are epidermal). Cotton-tipped applicators moistened with 90 % phenol were rubbed over the curetted area for 45 seconds, followed by dilution/neutralization with 70 % ethanol; the cycle was repeated once. A copper dressing (MedCu®; Technologiels Ltd, Israel) was applied in contact with the site, and a semi-compressive bandage was placed. Postoperatively, the patient was advised 24 hours of relative rest, to wear roomy footwear, and to use acetaminophen 1 g every 8 hours if needed.

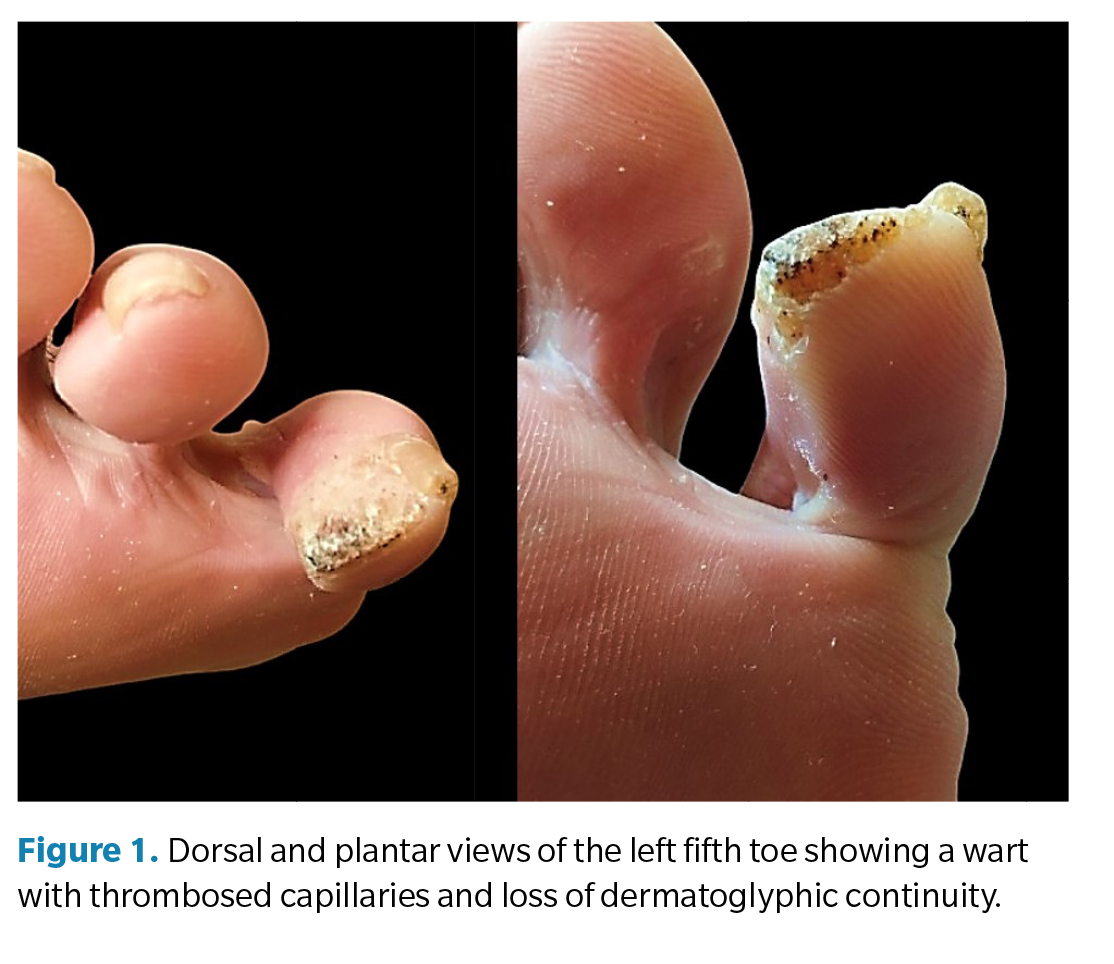

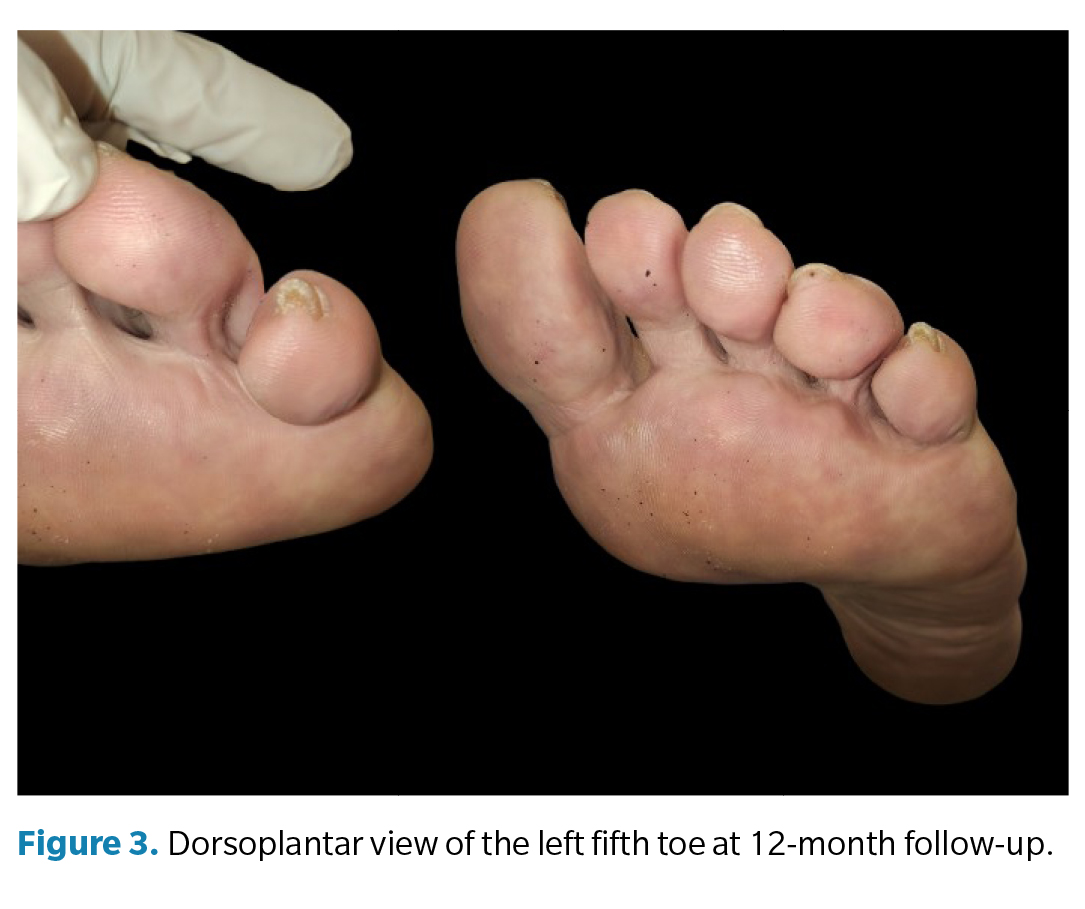

Daily home care was prescribed with silver sulfadiazine spray suspension (Silvederma®; Laboratorio Aldo-Unión SL, Spain) for 2 weeks. Histopathology confirmed a viral wart: “Sections of skin with marked surface hyperkeratosis with parakeratotic columns; epidermal acanthosis with prominent papillomatosis, hypergranulosis, and perinuclear vacuoles in keratinocytes of the Malpighian layer”. At the 3-month follow-up there was no lesion (Figure 2). At 12 months, no wart was evident and dermatoglyphics of the fifth toe were restored (Figure 3).

Discussion

Surgical approaches vary with wart location and size. En bloc excision was avoided in this case because of ~20 % postoperative recurrence(11).

Although numerous physical, chemical, and surgical methods have been described, combination therapy may reduce recurrence risk, as in our case (curettage plus phenol). Phenol is widely used by podiatrists in partial or total chemical matricectomy; its evidence base for warts is more limited, yet several authors report phenol or other acids as adjuncts within multimodal regimens.

Banihashemi et al. (12) conducted a clinical trial in 60 patients with common hand warts: half received 80 % phenol weekly up to 6 weeks or until clearance, and the remainder underwent cryotherapy. In our case, two applications of 90 % phenol were performed intraoperatively on the same day. The authors concluded both treatments were effective, simple, and painless. In our refractory case, phenol was effective in combination with curettage; a single technique might have failed, given prior unsuccessful multipuncture despite reported efficacy > 70 %. Patient age, viral latency, and delayed or absent immune response may explain failures(13,14). García-Clavería et al. (15) reported a 24-year-old man with mosaic plantar warts treated with the multipuncture technique plus the same adjuvant used in our patient, with favorable outcomes—contrasting with our recalcitrant wart.

Hoffner et al. (16) used 35 % trichloroacetic acid with curettage for flat warts, noting an effective, low-cost option with satisfactory cosmetic results and no recurrence at the follow-up. In our case, phenol with curettage was likewise effective and economical, and the treated fingertip pulp matched adjacent toes cosmetically.

Similarly, Dalimunthe et al. (17) treated multiple warts in the same patient using two methods: electrodissection plus surgical curettage for some lesions and 80 % phenol for others. Electrodissection/curettage was performed once; phenol was applied weekly until clearance or for a maximum of 6 weeks. At 6 weeks, lesions treated with electrodissection/curettage had fully healed, whereas phenol-treated warts showed a 35.3 % recurrence rate. In our case, combining 2 techniques achieved resolution.

Simamora et al. (18) presented 2 cases (plantar and palmar) treated by curettage plus policresulene, a polymolecular organic acid; in one case it was applied postoperatively. Hypopigmentation was observed, suggesting prolonged exposure or dissection into the dermis. In our case, we avoided the dermis and limited phenol exposure to two 45-second cycles, with no color change relative to adjacent skin.

In conclusion, 90 % phenol combined with curettage appears to be a useful option for common warts and may be considered among therapeutic alternatives. In this case, it was achieved clearance of a recalcitrant wart without recurrence. Further studies are needed to evaluate the efficacy of curettage plus phenol across wart types, considering disease duration, location, refractoriness, phenol concentration, and exposure time.

Conflict of interest

None declared

Funding

None declared

References